Is there a Tsui Hark paradox?

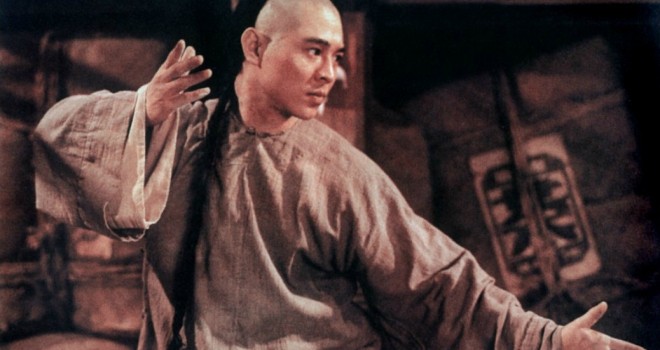

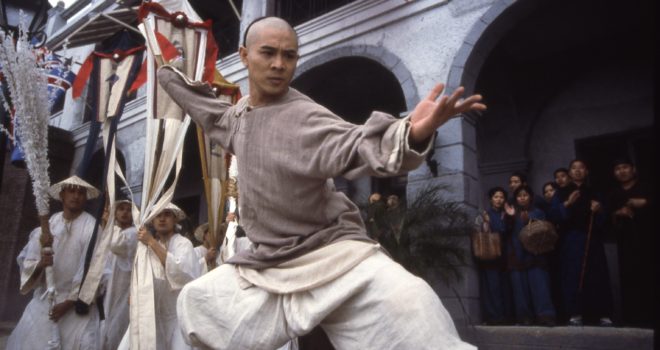

With fifty films clocked up as director and a good twenty more as producer over a forty-year stretch, the Hong Kong filmmaker stands, objectively speaking, as a colossus in the contemporary Asian cinematographic landscape. Yet, invariably since the beginnings of this prolific career(1), our access to his films is still hobbled in France by deficient and haphazard distribution – a shortcoming made good by perpetual catch-up sessions on DVD or Blu-ray. This dysfunction fuels confusion on what we know about the films of a cineaste whose name, with its whip-crack resonance, is arresting. Astonishingly, the rarity of his films seems to sustain both the popularity of a continually rediscovered oeuvre and the filmmaker’s aura. Although this popularity is certainly relative for the general public, who broad-mindedly venture onto cinephile territory, this rediscovery appears as a junction between two generations of enthusiasts for whom he opened the door of Hong Kong cinema, between the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. At the same moment – which also saw Hark’s critics concoct his anecdotal competition with John Woo whilst overlooking the fact that he had relaunched Woo’s career by producing the very films they were acclaiming –, there appeared another key facet of the filmmaker, who continued his trajectory unperturbed, and revealing on his way Jet Li in The Master (1989), bringing back the patriarch King Hu in Swordsman (1990).

In 1984, Tsui Hark and his producer wife Nansun Shin set up the Film Workshop production company. In the man that we had until then only seen from afar, this turning point revealed an entrepreneur concerned for his independence, who knew how to surround himself with multiple skills in order to ramp up his intentions to the full capacity of their ambition: revive and update the forms of a popular and innovative Chinese cinema without losing a tradition to which he feels a melancholy attachment. The consecutive successes of two historical films, Shanghai Blues (1984) and Peking Opera Blues (1986) immediately accommodated his desire for this all-embracing know-how. Many of Tsui Hark’s following films owe their critical success to this inspiration whereby director and producer aim in a single gesture for an equilibrium – although everything in the films vacillates – between entertainment and thought, a link between the present, an imaginary past and history…

Jérôme Baron

Read more

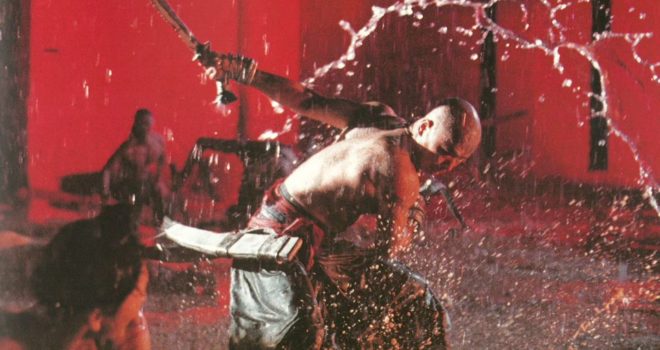

Indivisibly renovating and custodial, Tsui Hark’s “ebullient” cinema shapes a succession of emblematic prototypes that evidence the vitality of Hong Kong cinema during those years. The experiments also crystallise a heritage in which Wu Pang, Chu Yuan, Li Han-hsiang, King Hu or Chang Cheh coexist. At first sight, action is the playful driver of the spectacles orchestrated by Tsui Hark. But in light of his remakes (New Dragon Gate Inn, Green Snake, The Lovers, The Blade…) and the stories he himself extends as sequels (Once Upon a Time in China, Zu, Warriors from the Magic Mountain, the three adventures of Detective Dee), the characters replaying their life to the limits of their physical and moral capacity, their magnificent exploits, seem like resurrections and repeated desperate leaps over the void – a sign of their ultimate resistance to the weight of the past and the unpredictable blasts of history. Each time, we hope for their victory as they exhaust themselves only to gain time before engaging in their next combat. All of Tsui Hark’s characters know this in advance or discover it. This vast whole, which seems like an eccentric offbeat shamble, and the flimsy coherence of some stories could well be the expression of an inaccessible appeasement, the intense speeds simply acting as a dust screen to hide a torment that has reached maturity. His virtuoso The Blade (1995) and Time and Tide (2000) are undoubtedly forms that push this logic to its extremes. Blocks of pure energy, bordering on illegibility, they seem to draw their prodigious power from the combustion of what they set in motion. With their profound darkness, these two films constitute – again paradoxically – beacons illuminating Tsui Hark’s path. The first, a shady and violent remake of Chang Cheh’s One-Armed Swordsman (1967), was made two years before Hong Kong was transferred to China. In 1990, when questioned about this upcoming event and the situation of local cinema, Tsui Hark said he had no idea what would happen: “No one has answers. Not even the Chinese. Not even God”. He said his wish was to continue his career where he was settled and criticised the excessive number of films being produced in an already saturated market, including a flock of avatars who copied formulas without understanding them and exhausted the genres. But in Hong Kong things always move faster. Seven years later, two years after The Blade and at the very moment the territory rejoined the Chinese fold, Tsui Hark made his first American film, Double Team, with Jean-Claude Van Damme. Hollywood had understood since the early 1990s that Hong Kong cinema was spearheading the future trends of action cinema and offered itself as a way-out of the film industry’s crisis in the former British colony. With varying degrees of success, Ringo Lam, Kirk Wong, Peter Chan, Ronny Yu and Tsui Hark all followed John Woo, who made his first Hollywood film in 1993. It soon became clear that the man from the Film Workshop, driven by his appetence for control over all the stages of his filmmaking, was not going to integrate. His American adventure came to a sudden end. Time and Tide is the film of his return. The idea for the film was murmured to Tsui Hark by the lyrics of a song he listened to over and over again, a melancholic evocation of the transition from a happy life to an insipid age. Reason enough to return to Hong Kong whatever the price. We are in 2000 and Time and Tide is an event that marked the history of action cinema. Difficult to summarise, the plot involves a succession of reversals, double-bottoms and narrative stunts that are amplified by the ingenuity of the action scenes, where an insane visual mise-en-scène hurls bodies and objects into an unstoppable chaotic dance – unless the intention is to describe the efforts required to be born again in a film crowned by two pregnancies. The finale resolves nothing and, in an ironic piece of bravura, conjoins a furious settling of scores and a birth.

The cinema of Tsui Hark is that of a bygone age, an impossible consolation, a bitter fight to let us glimpse and relive our lost innocence, if only for an instant. It is not by chance that most of these characters are wandering, lost, floating: waiting for an answer.

Jérôme Baron

1) The Butterfly Murders, his first film, made in 1979.

(2) Tsui Hark consecutively produced five films by John Woo between 1986 and 1989: Heroes Shed No Tears; A Better Tomorrow 1 and 2, The Killer, Just Heroes.

(3) Cahiers du Cinéma, No.427 January 1990, “Hong Kong Blues” by Nicolas Saada, pp. 71–75.