SHOCHIKU STUDIO IS 100 YEARS OLD!

In 2011, we celebrated the centenary of Nikkatsu, the first-born of the major Japanese film studios, with a retrospective of twenty-five films. Two weeks before the opening of the 33rd Festival des 3 Continents, the Cinématographe had screened a cycle of ten films dedicated to the well-known “romans-pornos” that the studio had produced in an effort to stave off bankruptcy in the early 1970s. While our knowl- edge of Japanese cinema has grown over the dec- ades, we are admittedly still far from having taken stock of one of the world’s richest cinematographic heritages. Since its inception, and on its own scale, the Festival des 3 Continents has frequently endeav- oured to highlight the singularities of Japanese cin- ema’s invaluable legacy. Such was the case in 2012, when the Festival programmed the complete works of Shinji Somai, a barely known director, yet pivotal figure in the Japanese cinema of the 1980s.

For many, Shochiku is Mount Fuji and… Yasujiro Ozu. When the company first set up in 1895 (yes, indeed!) it specialised in producing kabuki performances, and decided to launch into filmmaking only in 1920. The first appearance of Mount Fuji on the Shochiku logo came later, in 1936. 20th Century Fox had its golden letters and monumental projectors sweeping the sky, MGM its roaring lion and Ars Gratia Artis motto, while the Japanese company appropriated the most sacred of Japan’s summits as a promise of quality and sign of prestige likely inspired by Paramount, which had opted for the silhouette of Mount Ben Lomond (Utah) in 1914. Moreover, Shochiku’s founders, Matsujiro and Takejiro Otani, had sent their younger brother to scout the United States and Europe during the 1910s. But this unmistakable blason aside, Shochiku did indeed reach the heights foreseen. Although the three masters, Kenji Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse and Akira Kurosawa, made films for the studio – Kurosawa only two –, it was Yasujiro Ozu who remained Shochiku’s iconic filmmaker. He spent thirty-five years of his career (1927-1962) with the studio and made fifty-two of his fifty-four feature films there. Almost contemporaneous, Naruse trained at the studio as assistant director mainly to Gosho. Even so, he made twenty-four shorts and features over a short stretch from 1930 to 1934, before being pushed out by Shiro Kido, then director of Shochiku studios in Kamata in the Tokyo suburbs, as Kido and the film- maker were finding it hard to reconcile their visions. Later, Kido justified this exclusion: “Shochiku had no need of two Ozus”. We know what Ozu said many years later about Naruse, whose Floating Clouds (1955) he so admired that its shattering effect on him made him doubt the value of his own work.

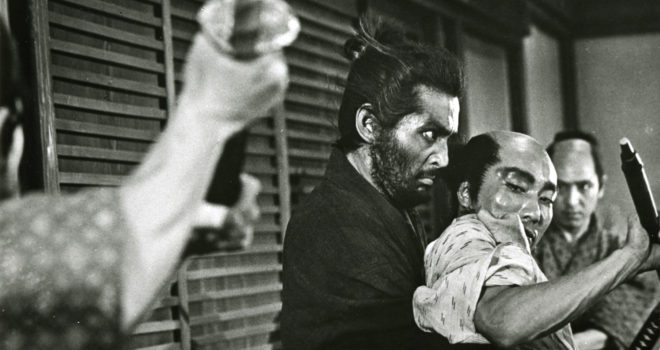

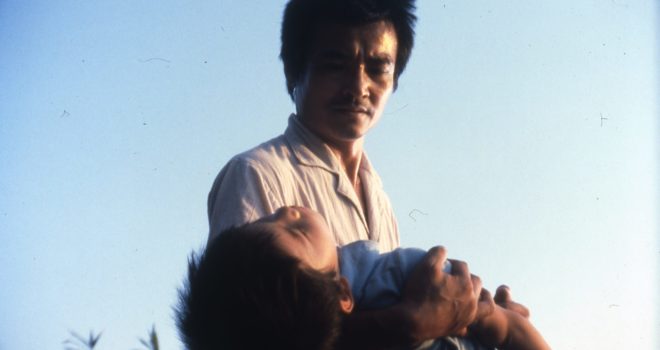

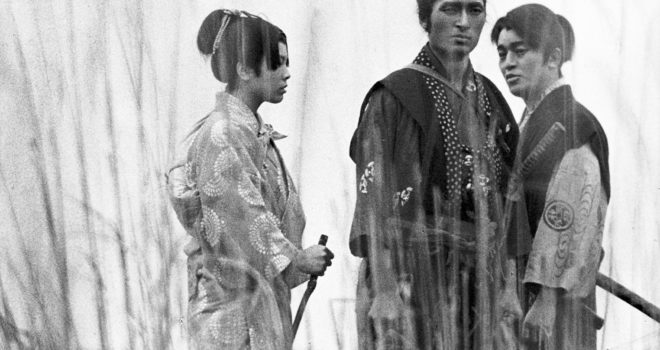

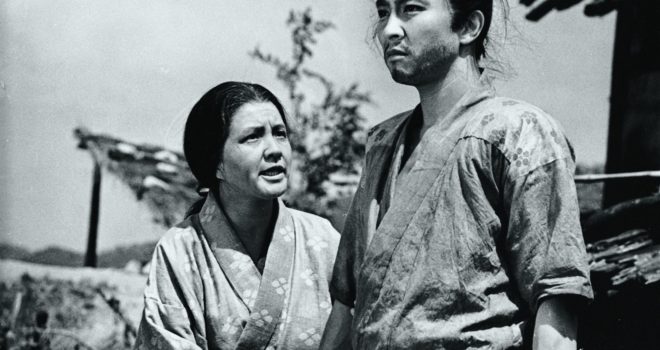

Beyond the anecdote, the works that these two names evoke shed fundamental light on Shochiku’s positioning and perhaps to some extent on the reasons for its longevity. Out of the major historical studios that engaged in fierce competition at various points in their history, the only ones to survive alongside Shochiku are Nikkatsu and Toho (Toei only appeared in 1950). But one of the most valorous con- tributions of the now 100-year-old company was its extraordinary capacity to return to an unchanging motif – the everyday life of simple folk – in order to better relaunch it. And this constancy of Shochiku was what enabled, almost paradoxically, a profusion of aesthetics which found their most accomplished popular expression in Heinosuke Gosho, Hiroshi Shimizu, Keisuke Kinoshita and, much later, Yoji Yamada. With Ozu, and above all his stylistic developments, then the intermediary generation of Yuzo Kawashima and Masaki Kobayashi (first working as Kinoshita’s assistant and collaborating on several of his elder’s film scripts), who in many ways foreshadows the Japanese New Wave that Shochiku helped to launch by producing the first films of Nagisa Oshima (3 Continents 2007 retrospective), and with Kiju Yoshida and Masahiro Shinoda, the studio was constantly able to nuance the palette of its gendaigeki (film genre set in the modern world) and its shomingeki (a sub-genre inherited from popular theatre, whose characters are mostly lower-middle-class Japanese), oscillating between melodrama, drama and less easily classifiable works (Kawashima), or a more abrupt realism like Kobayashi’s Black River. And although the company was far from being the only one to produce this kind of film, it is decidedly difficult to distinguish the pages of cinema history written by the studio and the feeling that these films go beyond their own fictions to tell the story a country. This is the thread that we tried to lay down when building this programme, which willingly lets some noisy counterpoints ring out, giving back a place on screen to the films of Hideo Gosha, whose influence is detectable from Miike to Tarantino, or to the equally rare Yoshitaro Nomura, which opens the programme.

And then, there are also the faces that become more familiar with each showing – the faces of Kinuyo Tanaka (who, as a director, made her final film Love Under the Crucifix with Shochiku), Hideko Takamine, Chieko Baisho, Chishu Ryu, Tatsuya Nakadai, to name but a few, and the disquieting conviction, as we catch their eye, of being seen by the films rather than discovering them.

Jérôme Baron