While a huge amount of books on the history of American film studios makes it possible to grasp the evolution of the relationship between art and industry within the Hollywood system, we only have a very fragmented knowledge of similar issues in Japanese cinema. However, in recent years, a spate of new and valuable books have been published, mainly in English. The term “industry” is suitable to define the predominant film production system in Japan which is based on a model inspired by the American experience. Japan produced as many as 600 films a year twice in its history, first at the end of the 1920s, then in 1957.

How can we explain the gaps in our knowledge of Japanese films? The discovery of the genius of Japanese cinema did not happen until the 1950s, a decade often considered as an economic and artistic golden age. The fact that this was a belated discovery was not intentional. In Europe, the revelation of Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, Teinosuke Kinugasa’s films, followed by Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse and Kon Ichikawa’s works, took place almost at the same time as the discovery of the daring films of Oshima, Yoshida, Imamura, Shinoda, Teshigahara and Hani. The latter generation of film-makers was immediately met with enthusiasm in the context of the intellectual and aesthetic agitation of European and Latin American film new waves. In the fervour of the sixties, the content and the relevance of these films temporarily prevented any possibility of a retrospective examination.

A number of events, such as the 1923 earthquake, great fires, World War II bombings and, to a lesser extent, pure negligence limited the access to films made during the first four decades of Japanese cinema, as well as to non-filmic sources essential to the building of solid knowledge. Cultural and linguistic issues specific to Japan sometimes made it even more difficult to grasp the structural realities of its film industry compared to others. For a long time, such issues had been a hindrance to the international distribution of Japanese films. Although it allowed some degree of foreign, especially American, influence to filter through its borders, Japan developed its own cinema according to a strong insular bias based on identity, with the studios showing no interest in exporting their production.

One of the delightful vocations of a film festival like ours has always been to contribute to a better understanding of some aspects of the so-called “classics” through screening forgotten or unavailable films. The wealth and diversity of a major film industry such as Japan’s never cease to surprise us, making it necessary to update our knowledge of it again and again. Nikkatsu’s hundredth anniversary seemed a good opportunity to do so, especially as the studio wished to display its concern for its own heritage and history – perhaps the most turbulent in Japanese film history. We are convinced that the discovery of such films allows us to better understand and question some issues of our own contemporary cinema. Interested film-goers will be struck by the eclectic nature of our programme. However, the selection, which includes early modern sword films of the 1930s, action films of the 1950s and “roman-porno” films of the 1970s, will allow viewers to create links between present-day imagery and its origin in history.

From period dramas to contemporary realities

Initially called Nippon Katsudo Shashin, Nikkatsu is the oldest major studio in Japan. Established in 1912, it was the result of the merger of four companies which, like the American Motion Picture Patents Company, wanted to create a monopoly on the Japanese film market. Although this proved to be a failure, Nikkatsu quickly became instrumental in the industrial boom of Japanese film production. The major investments it made resulted in the simultaneous running of two studios in Kyoto (Daishogun) and Tokyo (Mukojima). Films found a natural outlet in the theatres owned by the company.

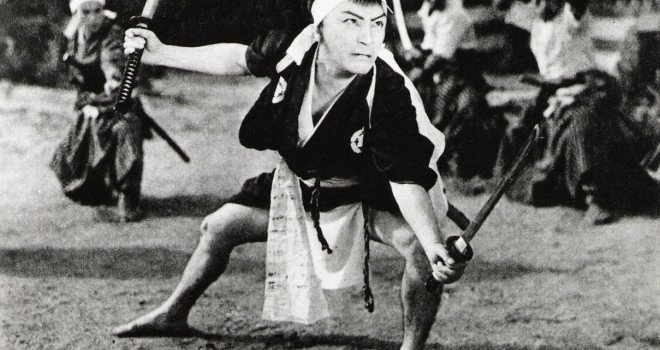

Yet Nikkatsu really owes its fame to Matsunosuke Onoe, the first great star of Japanese cinema, whose reputation was established by director Shozo Makino. Historical films, or jidaigeki, were the majority; however, the sword film sub-genre (chanbara) became more and more popular as viewers discovered Onoe’s stunning performances. Makino and Onoe made almost a hundred films together from the 1910s to 1926, when the actor died. After the 1923 earthquake, Nikkatsu concentrated its production activities in Kyoto. While it kept making historical films, the studio produced films focusing on contemporary issues (gendaigeki), like its rivals. Such films were met with very good audience reception. This was when Kenji Mizoguchi made his debut as director for Nikkatsu. Neglecting the melodramatic tone of some contemporary films, he cast a realistic look on popular and middle classes. Few films remain from this early period of the film-maker’s work, except for a partial version of Tokyo March (1929), restored by Cinémathèque française, and Home Town (1930), Mizoguchi’s oldest remaining full film and the first attempt at sound film in Japanese history. From 1923 to 1930, Mizoguchi made about fifty films for Nikkatsu. He left the company in 1932 and made his very last film there in 1934, The Pass of Love and Hate (Aizo-Toge). Although the studio employed highly talented directors such as Minoru Minata, Tomu Uchida, Ito Daisuke, Tomotaka Tasaka, Masahiro Makino or Hiroshi Inagaki, these were often tempted to work for other companies attracting them with better pay.

Nikkatsu found it hard to adapt its production methods to the realities of the 1930s. In 1934, the acquisition of a new studio in Tamagawa, in the Tokyo district, was consistent with the vision of the company’s new chairman, Sadatomo Nakatami, who asked a number of talents to come back to the studio to foster prosperity. Sadao Yamanaka was one of the emblematic geniuses of the time. While Ito Daisuke outstandingly contributed to the revival of the sword film, Yamanaka made landmark films in the history of Japanese cinema and influenced directors like Mizoguchi and Ozu. Only three films remain out of the twenty-three he made over seven years (Yamanaka died of dysentery on the Manchurian front in 1938). The parodic dimension of A Pot Worth a Million Ryo (1935) and the sensitivity of Kôchiyama Sôchun (1936) are enough to show how Japanese film buffs are attached to this director. The great actress Setsuko Hara, admired by Natuse and especially by Ozu, is young Onami in Kôchiyama Sôchun, one of her early appearances on the big screen.

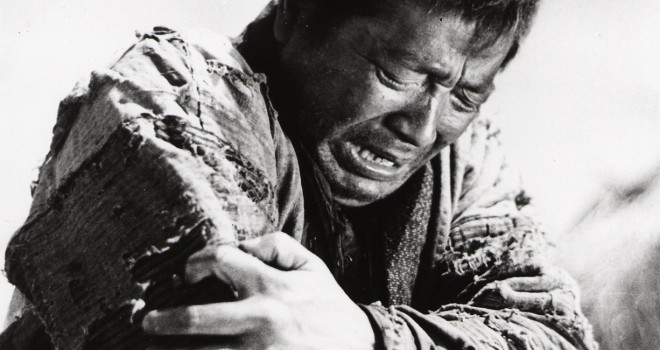

In spite of its stars like Denjiro Okochi (Ito Daisuke’s Jirokichi the Rat) or Tsumasaburo Bando (Masahiro Makino’s Chikemuri Takadanobaba) and the success of unusual films (Masahiro Makino’s Singing Love Birds), Nikkatsu had trouble with the competitiveness of the Japanese film industry, especially with its rival Shochiku. In 1942, general manager Kyusaku Hori neglected production in favour of a new entity called Daiei, producing films within the Shinko and Daito independent studios. However, in 1939, Nikkatsu made two daring war films, considering the military and nationalistic context of the time, Tomotaka Tasaka’s Mud and Soldiers and Tomu Uchida’s Earth, which the company hardly knew was being shot, defying the studio’s and the government’s authority.

Contemporary, urban and “bad taste” films

From now on, Nikkatsu decided to focus on distribution. Yet this temporary shift in its activities was also the key to its new prosperity as the company specialised in distributing American films in the post-war years. Glamour and action became profitable, as the number of foreign films screened in Japan doubled from 1951 to 1953. After a troubled period of traumas, social unrest and censorship resulting from the American occupation, the Japanese people felt a basic need for entertainment. This was going to be the most prosperous period for the national film industry.

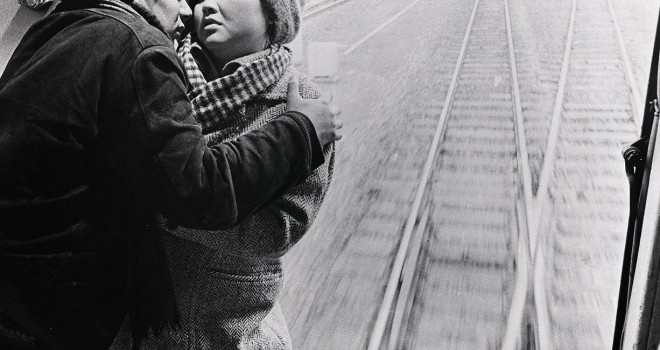

Nikkatsu revived its production branch in 1954. The five other major studios (Toho, Shochiku, Daiei, Toei and Shin Toho) reacted strongly to the move, fearing they would lose market shares and, possibly, talents who might want to join the new outfit. Nikkatsu tried various genres with varying success, with stylistically American-influenced films. One film became the model which inspired a great number of films to come, Takumi Furakawa’s Season of the Sun (1956), based on Shintaro Ishihara’s acclaimed novel. This controversial film challenged the treatment of teenager stories common in Japanese cinema at the time. A whole generation of viewers identified with Yujiro Ishihara, the novelist’s own brother soon to become the greatest Japanese film star. His persona was somewhere between James Dean and Elvis Presley. In 1956, the so-called Sun Tribe produced its first major achievement with Ko Nakahira’s Crazed Fruit, in which Ishihara co-starred with Masahiko Tsugawa (his elder brother in the film) and Mie Kitahara (beautiful Eri). At the time, the film was acclaimed by François Truffaut, then a film critic.

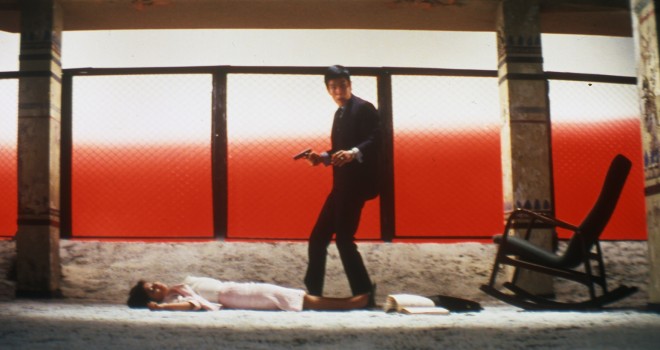

Often overshadowed by the emergence of great film-makers such as Shohei Imamura and Seijun Suzuki, a number of directors contributed to Nikkatsu’s revival with B-movie type of films, during the prosperous years of action cinema in Japan. These are Ko Nakahira, Yuzo Kawashima, Kastumi Nishikawa, Toshio Masuda, Koreyoshi Kurahara and, later, Yasuharu Hasebe, almost all of them being unknown in the West. For a while, Imamura (Murderous Instincts, 1964) and Suzuki (Tokyo Drifter, 1966) were able to display their auteur tendencies at Nikkatsu because the firm allowed almost any breach of moral behaviour, as long as budgets were kept in line. On the whole, the Nikkatsu style (or Akushon, for “action”) was cosmopolitan, contemporary, urban, “bad taste” and glamorous. In the midst of Japanese reconstruction, the heroes of these films loosely based on American genre films were yakuzas, young rock fans in love and contract killers. Yet two films of our programme do not fall into this category: Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate (1957), a comic take on jidaigeki and one of Yuzo Kawashima’s most successful films, and The Dancing Girl of Izu (1963) Katsumi Nishikawa’s superb melodrama, based on Yasunari Kawabata’s first novel.

In the second half of the 1960s, the penetration of television in Japanese homes triggered a major crisis in the local film industry. Staunch rivals as they were, studios were all affected by the new situation. Anxious to make money, Nikkatsu tried to rekindle the appeal of its stars (Akira Kobayashi, Joe Shishido) and introduced new faces to the big screen (Meiko Kaji, Tetsuya Watari or pop star Akiko Wada). But the so-called New Action films failed to replicate the previous decade’s commercial successes.

In 1971, the firm took the decision to focus on low-budget erotic films (between 100,000 and 150,000 euros), usually shot within a week. Nikkatsu’s roman-porno genre was born, with films made in various styles over the years until the late 1980s. The new trend mainly owed its success to directors who were to have a deep influence on Japanese cinema: Tatsumi Kumashiro, Noboru Tanaka, Chusei Sone, Masaru Konuma, and later Shinji Somai who made only one such film. Roman-porno is anything but a second-rate film genre as it undoubtedly contributed to film art in Japan in the 1970s, in a way which is totally unknown in other parts of the world. Taken seriously, even in the context of commissioned films, eroticism became a means to question the Japanese identity from a social and cultural point of view, to reflect on its present and future state, considering sexuality in all its forms as a permanent feature of human activity. Erotic themes made it possible to explore social classes, different places and different times through the body, desires and taboos. Roman-porno was also crucial in training a large number of film-makers of the next generation: directors learned the trade as assistants, directors of photography, continuity girls and editors got trained, often on low salaries.

The twenty-six films of our programme provide but a partial history of the oldest and most famous Japanese film studio. Most of these films have never been seen before in France, which shows how important Nikkatsu’s heritage is and how much remains to be discovered in Japanese cinema. Such an eclectic selection is an opportunity to display images and forms which have had a definite influence on other film-makers. It seems to us that rediscovering these films was an occasion not to be missed.

Jérôme BARON