Bolstered up by recent international, and sometimes controversial, successes from directors Guillermo Del Toro, Alfonso Cuaron, Alejandro Gonzalez Iñarritu, Carlos Reygadas and Amat Escalante, themselves followed by an even younger group of new film-makers, Mexican cinema seems to be going through an upbeat phase, despite deep structural problems. However, whenever Mexican cinema is discussed, one name keeps reappearing – Arturo Ripstein’s. And this obviously has less to do with a forty-year long career than with the singular nature of the unusual worlds the film-maker has left in our memories. Memory is indeed a fitted term as, although Ripstein enjoys recognition from film-goers worldwide, his films can hardly be seen on our big screens. This is why our retrospective of his work in his presence, and the presence of Paz Alicia Garciadiego, his partner in life and the scriptwriter of his last fifteen films, is not a luxury but a happy twist of luck.

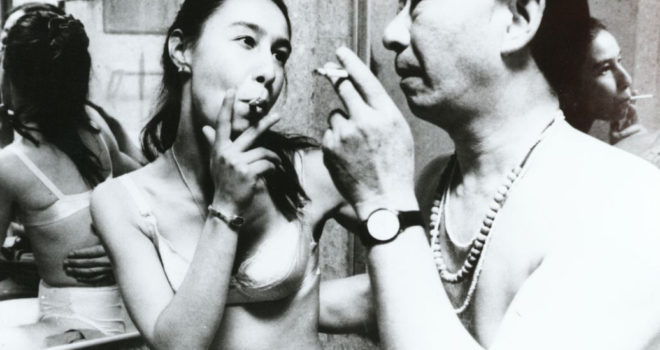

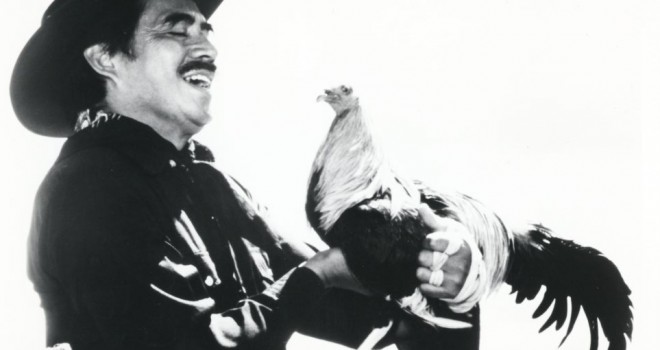

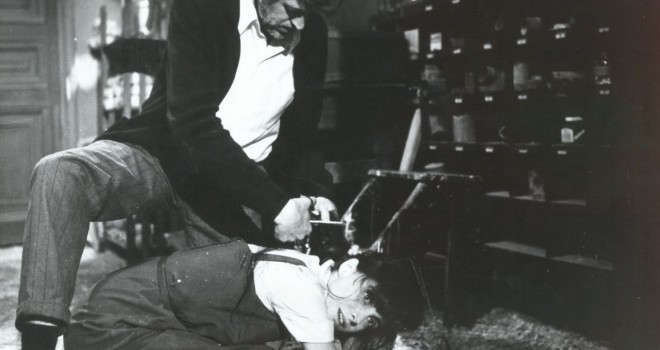

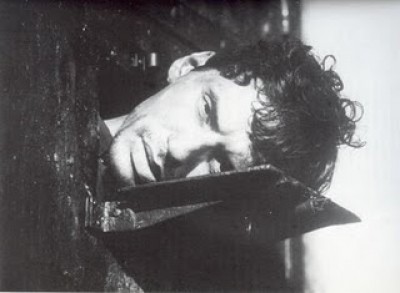

The title of one of Ripstein’s films could sum up the whole of his work: Principio y fin. Under the aegis of the implacable fate of reality, the beginning of each film heralds its ending. In this particular film, a debt-ridden father brings about the social descent of a middle-class family until it morally and physically dies and, with it, a number of people. Arturo Ripstein is not a master of suspense as such. However, using melodramatic themes common in Mexican cinema, he goes deeper into these themes, seeking an unpredictable boosting. Luis Buñuel – Ripstein was a former assistant of his – also never tried to do away with melodrama. In a way, Rita Macedo (Nazarin, The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, The Exterminating Angel) bore its mark until the final revelation in Castle of Purity (1973). The characters we meet in Arturo Ripstein’s films might be said to feel uneasy wearing the clothes society or nature wants them to wear. For them, the world is an alienating prison (social, spiritual, sexual, economic) and they live with the consciously illusory hope that they could become other people than themselves. Such an unquenchable thirst for miracles that never happen bring them to have other wild dreams in gambling, in sex, in crime… This is where some aesthetic features of Ripstein’s work take their full meaning. The film-maker does not resent using artificial tools (sets and props, almost histrionic acting) which are as much unavoidable elements of his directing approach as the visible signs of the unlikely narrative everyone builds for themselves in order to survive. Shots turn into very long takes, in comings and goings showing that there is no way out. Ripstein’s films are labyrinths. The scratching his characters inflict upon reality to get out of it does not leave that reality, and us, unscathed. Yet the film-maker does not take it upon himself to save them at all cost, which would be highly demagogic, since they cannot save themselves in the first place.

How, then, does the film-maker consider Mexican society? In this respect, Ripstein’s films are never vehicles for a sociological or exemplary reflection of the world. Rather he allows himself to tamper with reality a little, a prerequisite for any form of art and any desire to make fiction films. Not that his films have no connection with reality whatsoever. Ripstein’s documentary on the famous Lecumberri prison, El palacio negro, is a good example. Yet the harshness of Ripstein’s films does not mean that they can be reduced to a single interpretation. They are always rife with multiple possibilities. Here everything seems possible, even the worst.

Jérôme BARON