Cities, now of a metropolitan size, are continually showing off their spectacular dimensions, staging the result of their amped-up transformation. When it was born at the junction of the 19th and 20th centuries, the industrial and urban art of cinema found the most primitive of its scenes in the city. Since then, the mutual fascination between city and cinema has spawned an aesthetic adventure with multiple and lasting ramifications. It could even be tempting to find there the material for a different history of cinema. As Serge Daney wrote on the subject: “The city has inspired cinema with the elementary forms and reflexes of the perception of the world.”

Films have spread the cities’ bustling sounds and transformed the real or fictional image of places we will never visit into an imaginary that we can make our own. Some of these cities have returned to us from a resurrected and fantasised past (like Max Ophuls’ Vienna). Others are from a present filmed at a cafe counter or among passers-by (Paris of the New Wave). Others rearrange their appearance and the density of their urban networks to fit the fears and obsessions that we project for the future (Fritz Lang, Otto Hunte and Eric Kettelhunt’s Metropolis extends into Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner). We could continue at leisure to track the points where cinema and city conjoin their movements, where films invent their own scales of the city, where they point out invisible frontiers under the vast superficial flows, detect convergence lines, sense off-screen worlds. Cinema has made the homo metropolis into the conscious spectator of his own condition, it has released in him the possibility of a toing-and-froing between the objective world and the subjective world.

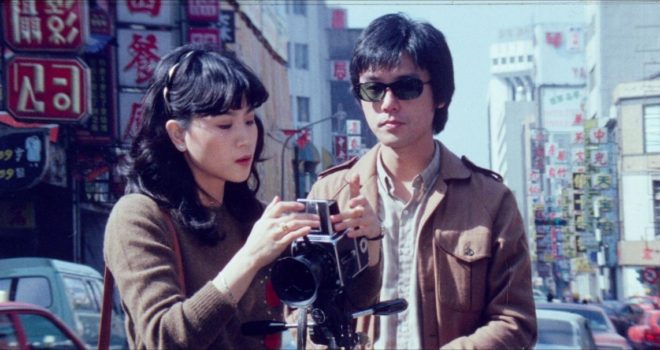

For most of us, our first images of Taipei, and even perhaps of Taiwan, probably date back some thirty years to the time that we discovered with surprise the New Taiwan Cinema, which suddenly appeared like an uncharted island on the cinephiles’ map. This cinema was all the newer as we knew absolutely nothing about it. Until then, only a few cities in East Asia such as Tokyo, Shanghai and Hong Kong had any substantive cinematographic reality for the distant observers that we were.

Read more

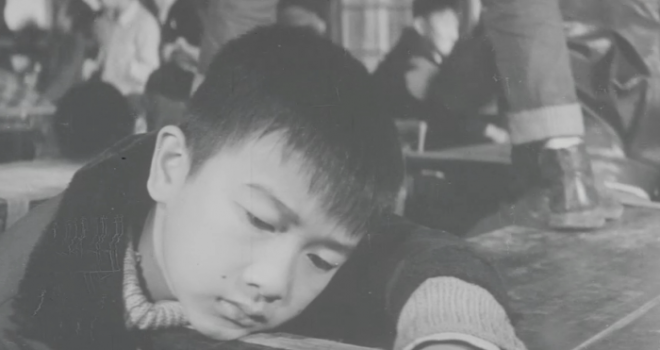

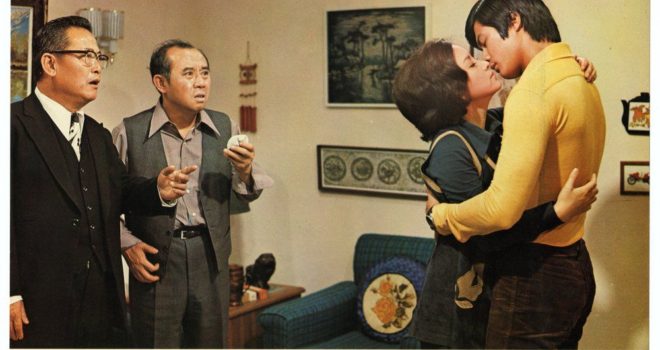

Given Taiwan’s small size and mountainous terrain, the location of Taipei (literally “The City of North Taiwan”) probably favoured it as the island’s natural capital. It firmly established itself not only as the country’s political powerhouse but also as its economic and cultural hub and more importantly over time, as the convergence point, the spasmodic crossroads of displaced (hi)stories that give Taiwan its special and cosmopolitan identity. Crisscrossing waves of successive migrations spanning three centuries, fifty years of Japanese occupation, and the indigenous Taiwanese aborigines with their own culture, who now have a firmly recognised place: Taipei city concentrates a dense body of stories deposited like the alluvium of the river Danshui on a bed of lush vegetation. Building there often means reconstructing, as apparent in the symbolic and exemplary transformations/disappearances characterising the city’s geography. At its cardinal points, the vestiges of the old city gates: the preserved original North Gate, the West Gate razed along with its walls by the Japanese, the South and East Gates refurbished in the “Kuomintang style”. The river Xindian runs through the city separating Taipeil from New Taipei City. As a city that has known and still knows how to assimilate, Taipei has rebuilt itself on the basis of multiple influences and swift adaptation to development models that have fast-tracked it into becoming a modern capital which challenges each individual to find their place there and also to create the means to write their own story. As a patched-up, hi-tech assemblage, Taipei exposes its seams, its electricity-spinning nerves and the massive veins of its overhead roads. The city’s stratified profile is what marks and seduces us most. The twelve films in the programme, Taipei Stories, in echo of the pivotal film by Edward Yang, paint a subjective picture of four movements whose directions are taken from a much broader corpus. Films by well-known authors (the already cited Edward Yang, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang) are screened alongside those by directors who are lesser known or unknown to European audiences, such as Mou Tun-fei’s I Didn’t Dare to Tell You (1969), which had still not been screened in Taiwan a few months ago. Each of these four movements has its own temporality rather than the hallmark of a set period. Yet, all these films – be it Early Train from Taipei (1964, the programme’s only Taiwanese-language film) or Goodbye Dragon Inn (2003) set in a run-down film theatre in downtown Taipei – offer us a condensed history of Taiwan cinema in which Taipei is either the setting or even the subject. From a burgeoning industrial city of the 1960s to the almost forty-year-long biography of Kuei-Mei, a Woman (1985), the films slip one under the another when they are not looking at each other, as in the westernised love stories, The Young Ones (1973) and Cheerful Wind (1981), or in the middleaged female characters of Daughter of the Nile (1987) and, not included in our 40-film round-up, of Millennium Mambo (2001), both by Hou Hsiao-hsien.

Watching these films in sequence is also to understand them through the prism of a changing geology of the city, movements, gestures, words, desires, anxieties.

In an ever-expanding Taipei, the characters often seem to be like islanders. How so? The more the city spreads, the more it seems to be a fiction, an illusion, for those who experience it. Paradoxically, the characters seem either to find themselves there or be hemmed in or searching for a part of themselves whose remaining reality is nonetheless embodied by the island.

While one generation after another becomes Taiwanese, the nationals of today and tomorrow continue to question themselves about what meaning they can give to this to this penetrating singularity.

In night time over there, while we are in broad daylight, the conjoined energy of the flashing neons seems bent on conjuring up the opacity of a city whose narrow and often peaceful streets, rather than being a source of concern, seem to hide other facets of life. These are what cinema brings to light. And it is also what brings the city so close to us.

Jérôme Baron