BRAZIL, BRAZILS: DOCUMENTARY CINEMA

Brazil, Brazils — the quite aptly chosen title for the Year of Brazil in France constitutes a most adequate framework for an introductory text on Brazilian documentary cinema which will have a privileged position in this year’s Nantes film festival, focusing on the discussion of the realist aesthetics in Brazilian film. However, today it is more appropriate to talk about Brazilian cinemas (in the plural) rather than Brazilian cinema (in the singular), a term which is more relevant to the film production mainly originating from the major urban centres — Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Outside the quite different films made in these two cities, other film forms are being created in terms of aesthetics, themes, production models, in the southern, north-eastern, west-midland and northern States of the country, all with a tendency to consolidate regional production centres. Furthermore, judging from the films made in the last fifteen years, a large number of documentaries are remarkable for the fact that they primarily target theatrical distribution. Such a phenomenon, which used to be based on direct funding through the State organisation in charge of cinema. The current legislation favours private sponsorship through tax incentives: therefore, the corporate sector is the new decision-maker as to which films should be produced. Making fiction films today in Brazil is an entrepreneurial, rather than artistic, operation which tends, whether deliberately or not, to repeat already established aesthetic and narrative models. Whithout getting into a full discussion on this complex issue, which has no simplistic solutions, it seems that low-budget films seeking increased freedom in creative and thematic choices turn to the documentary form, thus spontaneously yielding a diversity of artistically recognised films. The odds are that, in the future, this mass of documentary films, which creatively depict contemporary Brazilian life, will become the main source of knowledge about the current historical reality…

From a historical perspective, this remarkable bulk of documentary films, typified by Bus 174 (Ônibus 174, 2002), aesthetically and thematically reflects the various stages of a growing and diversifying process in Brazilian documentary since the 1930s, when the first film-supporting State organisation, Instituto Nacional de Cinema Educativo (National Institute for Educational Cinema), was founded. Humberto Mauro was its first manager and made there dozens of educational documentaries on a large variety of subjects. Although he was only sensitive to the educational aspect of the documentary, Mauro intuitively developed an aesthetics based on tableaux of Brazilian society and marked by a genuine and romantic lyricism, which can also be found in fiction films. In the 1960s, the young Cinema Novo film-makers worshipped Mauro as one of the most advanced of our film-makers in the early “heroic stage”. The Ox Cart (Carro de Bois, 1945), also shown in Nantes, is one of the best examples of Mauro’s educational documentary production.

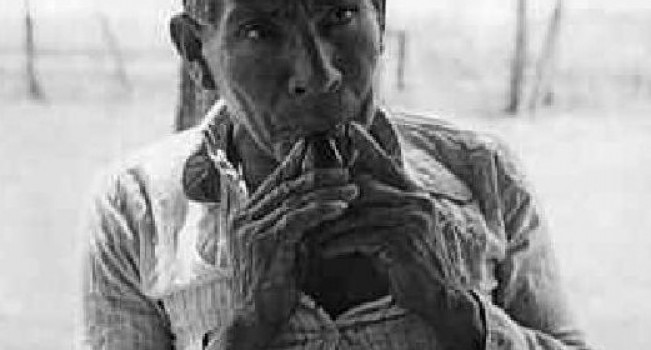

Another crucial moment in the early filmic interpretations of Brazilian reality, contrasting with the purely commercial fiction film production, is Orson Welles’s 1942 visit, when the outstanding director of Citizen Kane undertook, with his own money, the re-enactment of a saga of jangadeiros from Nordeste, called It’s All True and performed by non-professional actors. Unfortunately, the project was stopped in tragic circumstances and remained unfinished until Welles’s death. The negatives were found again in the early nineties and the film was finished with the help of the director’s former assistants. When we take a closer look today, we realise that this 1942 film is an impressive anticipation of the realist trend in world cinema. Welles’s It’s All True is to Brazil what Eisentein’s Que Viva México is to Mexico.

The 1950s were not particularly generous in documentary films. But Ana, a segment of the fiction film Rosa dos Ventos (The Wind Rose, 1957), directed by Alex Vianny and written by Jorge Amado, Alberto Cavalcanti and Trigueirinho Neto, is so influenced by a realist aesthetics that it can be considered as one of the first and best documentaries about the retirantes from Nordeste migranting southwards to keep away from the drought. Rosa dos Ventos is a curious international production made under Alberto Cavalcanti and Joris Ivens’s supervision, and funded by the East-German Communist Party!

The advent of Cinema Novo in the 1960s marked the beginning of a new trend of aesthetic proposals and specific production projects within the documentary genre. Cinco vezes favela (1962), a documentary made up of several episodes directed by Marcos Farias, Miguel Borges, Carlos Diegues, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade and Léon Hirzman, is a major film belonging to that movement, which was to influence the whole of Brazilian cinema to come. Directly influenced by Italian neorealism, Cinema Novo left an indelible mark on the aesthetic of Brazilian documentary film. Eduardo Coutinho, production manager on Cinco vezes favela and who was to become a most influential figure in contemporary world documentary film, defined the aesthetic paradigms of Brazilian documentary film, defined the aesthetic paradigms of Brazilian documentary films: “…a free style and a critical treatment of a theme connected to Brazilian reality. It is important to suggest solutions to our dramatic predicaments, to name the culprits, to raise the audience’s political awareness.”

However, the appearance of Cinema Direto (direct cinema) — a result of the synchronous recording of sound and picture on 16mm film stock —, at the same time, would help documentary films, both in Brazil and throughout the world, to gain the highest efficiency in language and production, which it still enjoys today. It continues to influence fiction films in their quest for the creative interpretation of reality. Cinema Direto was a radical break with the established ways and changed traditional narration. 16mm was more than just a technique; it represented the natural breathing of an art which was reinvigorated by the contact with the real world. This format made it possible for cinema and its history to really begin.

Cinema Direto spread out throughout the 1960s and the 1970s, was the basis for TV documentaries and hasn’t stopped evolving since. The replacement of 16mm by the digital format only amplified its universal appeal, while maintaining its basic aesthetic premises, rooted in the synchronous recording of sound and image. The aesthetic principles promoted by Leacock, Pennebaker, Rouch, the pioneers of direct cinema in the USA and in Europe, remain as valid today. Occasionally, as with Michael Moore’s films the impact of direct cinema is such that it goes far beyond genre classifications — whose borders are fictitious and aesthetically indefensible, as Alberto Cavalcanti and other documentary founding fathers always knew — and it has carved out a place of its own in the midst of so-called fiction films.

Brasil Verdade, Iracema, uma Tranza Amazônica, Os Doces Bárbaros, Terra dos Indios, Egungun, Bahia de Todos os Sambas, Cabra Marcado para Morrer, Terra para Rose are all vehicles for the direct cinema aesthetics, characterised by an authentic discourse which moves, breathes and occupies the frame, as it shows how human beings communicate, i.e. how they talk to each other. Proper authors use this revolutionary medium for their creative mediation.

Jom Tob Azulay, film-maker