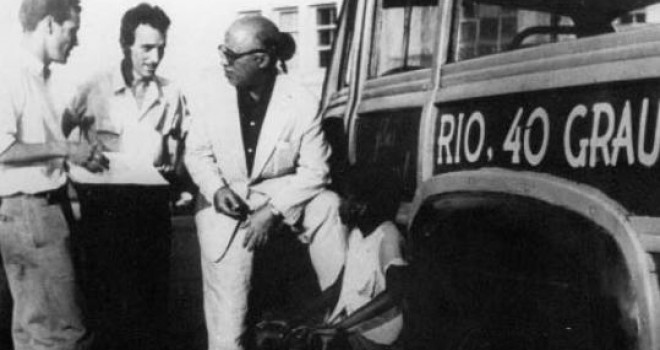

A distinctive film realism did not appear in the Brazilian film history until the 1950s. The comparison between Italian neorealism and films such as Rio 40° — which incorporate certain formal features of that European movement and bring about a subtler presence and investigation of the local social and cultural reality — is constant in classic essays. However, no clear definition of the word realism has ever been set, nor has its presence in previous periods of Brazilian film history been demonstrated, except on rare occasions when the so-called neorealist trend was precisely pointed out. Despite the fact that most films asserted some kind of a relationship with reality — a relationship imitating the theatrical and literary realism of the second half of the 19th century, which means that such films belonged mainly to classical narration—, the then dominant conceptual opposition in cinema do not concern the degree of realistic stylisation, but the supposed antagonism between studios and locations. We have become aware of the aesthetic and political value of a scene shot on an everyday location only through the conquest of the street, of the countryside, of the landscape, especially natural landscapes. With the advent of sound in 1933, interior scenes were preferred. Technical difficulties took crews back to the studios. Yet, frequent adaptations of stage plays led to an examination of bourgeois intimacy. A film such as Bonequinha de Seda (Silk Dolls) typifies this prevailing practice which remained in place until the late 1940s, even in more specific genres like chanchada (a kind of Brazilian burlesque comedy), with such as Fantasma por Acaso or Carnaval no Fogo. For a historian like Alex Viany, the “deviation” from this model is precisely in the use of natural locations. Some scenes from Favela dos meus Amores, João Ninguém and Moleque Tião gain in strength and authenticity through the contrast emphasised by the studio environment.

The persistence in finding neorealist features before the advent of neorealism would rather point at the presence of characteristics inherent to the Brazilian tradition, which would come in full bloom in the 1950s. Vianny’s point of view is perhaps an attempt to politicise the theme and, even more significantly, to support the existence of a specifically Brazilian realism.

During the same period, although it implied a totally different direction, Alberto Cavalcanti’s book Filme e Realidade (“Film and Reality”) articulated the ideology of the realistic purpose of cinema. The “wandering film-maker” didn’t advocate the concept of a realistic scene (filming reality as is), but the notion of a realistic treatment of the scene, which implied the development of a specific language. While he was in Brazil, under contract with the Vera Cruz, and then the Maristela/Kinofilmes film companies, Cavalcanti was linked to the setting-up of big studios and to the incorporation of a very naturalistic tone as far as the characters, the themes and the spaces were concerned. Imposing a genre, almost always in the metaphysical tone he loved so much, and a technique of composition creating a clear, clean and balanced image, ended up in jeopardising the realistic tendency; and the coexistence of contradictory strategies (shooting on location but still using the large studio reflectors, for example) produced something artificial. What remains is films which claim great pretension, but lacking aesthetic density and proper influence.

With less flourish and taking upon a completely different direction, at the end of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s, a number of films appeared which demonstrated a higher taste for everyday realism, with a more existential and documenting approach. There is some sort of Italian influence which producers, critics and film-makers such as Mário Audrá, Salvyano Cacalcanti de Paiva and Nelson Pereira dos Santos will later discuss. Those films are less indebted to a certain trend of Italian comedy (Risi, Monicelli, etc.), or to William Wyler’s tradition of psychological realism. However, Brazilian films use the analytical and fragmented cutting of the scene, instead of the recent Italian approach which favours the integrity of the action. Armando Couto was perhaps the film-maker who was the closest to the neorealist approach, through his depiction of the suffering migrant (and it isn’t just by chance that the migrant is Italian), his examination of unemployement in the middle of the industrial boom, his solidarity with the common man who is never discouraged even when faced with life’s difficulties.

This new form of realism appeared in films such as Estrala da Manhã, Caminhos do Sul and mainly Vento Norte, in which landscape is usedas an omnipresent visual icon, i.e. by putting the interaction of man with his environment at the heart of the narration. Incidentally, this also occurs to some degree in films made by the major São Paulo studios, especially by Vera Cruz. A film like O Cangaceiro is a perfect example; it emphasises the location elements — the mountains, the sky, the clouds — although it is more baroque than realistic (under Gabriel Figueroa’s influence). Scliar’s film is also noticeable for the way it gives a voice to southern fishermen and the exposure of social scandals. Directly revealing, or just implying, inequalities is the basis of urban film – Grande Momento or Rio, Zona Norte, for example —, as well as rural and coastal films — Canto do Mar or Ana, the Brazilian episode in Die Windrose; the first categoryal most always deals with the lower middle classes or the working class, the second category being concerned with socially rejected or marginalised people.

The tree of Brazilian film realism grew further through the depiction of suburban daily life in films like Alameda da Saudade, 113 or Agulha no Palheiro” which demonstrated the will to capture behaviours, languages and temperaments, rather than unfold a proper plot. Their scripts are miles away from fantasy, and don’t overemphasise the features of social contrast.These films focus on details, on a sophisticated scenography, on the gathering of specific popular types. They shed light on the little daily dramas, such as an unwanted pregnancy. As a counterpoint to the prevailing verism of ail these films, whose photography is marked by half-tones and neutrality, music remains in the background. Theatre actors were less and less used. Among other aspects, there were also, in the mid-fifties, boredom and the anxiety of a certain elite — made up of aristocrats or nouveaux riches — treated with psychological realism in films such as Ravina, Estranho Encontro, Cara de Fogo, A Estrada and Paixão de Gaucho.

Other films resist any sort of classification because of their aesthetic “fluctuation”. Most of them seem to share a decline of the studio aesthetic, increasingly out of touch with the naturalism of locations (the artificial aspect of the studio was then more and more considered as a negative element). Furthermore, film-makers sometimes flirt with the documentary, as in the jogo do bicho scene (an illegal lottery involving animals) in Amei um Bicheiro ; or they focus on situations about to disappear, such as the rural depiction of Canto da Saudade. Towards the end of the decade, the politicisation of the social representation becomes obvious in films like Redenção. Through such films, the realisms of the Fifties constitute a transition towards a more politically involved cinema, as Bahia de Todos os Sanros or Pagador de Promessas show at the beginning of the following decade. Until the very notion of realism or, more precisely, of realistic language was thwarted by the Cinema Novo winds.

Hernani Heffner

Assistant-Curator and Head of the MAM Film Archives.