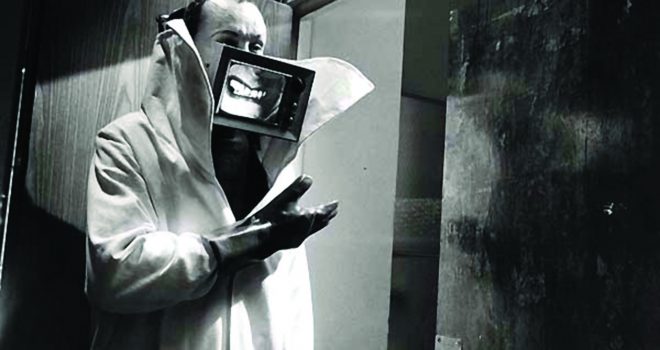

The manifestations of what relates to the fantastic in cinema seem easily identifiable. Everyone can pinpoint them as a genre or sub- genre because they are clearly stated as such (often on the film poster) in formulas that can seemingly be extended indefinitely: science- fiction films that can be expanded to a fantasy or legendary corollary, whose current versions come as super-hero or heroic fantasy films, horror or even gore films, ghost or reincarnation films, small and large monsters with apocalyptic intentions… Fantastic cinema draws much of its inspiration from a rereading of the leitmotifs that nourished the painting and, more importantly, the literature of the very end of the 18th century through to the beginning of the 20th century – from the Brothers Grimm to Andersen, from Edgar Allan Poe to Jules Verne and Oscar Wilde, from German Romanticism to the English Gothic novel (the birth of Dracula under the pen of Bram Stoker in 1897 is contempaneous with the advent of the Lumière Brothers’ cinematography and Freudian psychoanalysis). Fantastic cinema has become a lucrative den of mad scientists, evil spirits, monstrous creatures, the infirm, giant or mythological animals, fallen humans and zombies… This delirious cinematic procession of abnormalities, dystopias and inexplicable imbalances of reality has become a subject of popular fascination. While fantastic cinema basically owes its success to the spectacular and technological one-upmanship from which it has regularly benefited, it is one of the less noble genres compared to the status of comedy (now flying at half-mast), the melodrama or the western (now extinct). What must be underlined, however, is the inexhaustible store of meaning and imagination that it has offered to filmmakers with the most diverse cinematic intentions: from Georges Méliès to Victor Sjöstrom and Maurice Stiller, from Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau to Fritz Lang and Carl Theodor Dreyer, from James Whale to Jacques Tourneur and Alfred Hitchcock, from Louis Feuillade to Jean Epstein, Jean Cocteau or Georges Franju, from Riccardo Freda to Mario Bava and Terence Fisher, from Georges Romero to Roger Corman and John Carpenter, to the two Davids – Cronenberg and Lynch – through to Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and others. Reading through this non-exhaustive and disparate pleiad of filmmakers, we might even be tempted to lay the ground for a reread of the history of cinema viewed through the prism of the fantastic. By posing the waymarks for a genealogy that focuses on genre as a laboratory, this filiation would have the merit of helping us to deconstruct the conformist hierarchy between the major and minor modes, or to set the spectacular dimension and poetic inspiration face to face.

In other words, this list bears out a self-evidence: we need to take the fantastic seriously and take as a certitude that its success has given it a firm footing in the heterogeneity of everything it encompasses. The fantastic clearly stands out in that it is unattributable to any kind of good taste or overly subjective criterion, as its purpose is the exploration and expression of limits, an impassible threshold or aberration. As such, it opens fertile ground for thought, extricating itself from the constraints to which the genre seems to logically condemn it: the effect and the anecdote. And this list also gives it even greater reach insofar as it seems to reveal to us not so much a genre as a “fantastic cinematography”, according to the formula taken up by Jean-Louis Leutrat, and whose essence was in a way defined by Antonin Artaud: “cinema never comes into its own more than when it brushes up against this wasteland, this narrow borderland peopled by creatures carrying within them the (this) contradiction” of the living- dead. The cinema plunges us into darkness. Suddenly, a luminous irreality surges up to battle with night in the theatre where we have taken seat. An image without depth, translucid and recently dematerialised gives life to ghosts that so resemble us that we know they bear a truth about who we are. They bear the seal of our anxieties, guess our fears, our nostalgia, things now disappeared, our desire to see them reappear, to be somewhere other than in our lives, to believe the impossible. They know that cinema is akin to some ancient ritual, like that of the old stories recounted around a nighttime fire. The intervention of the fantastic opposes the natural order of things and events. It keeps us in silence while the film leads us towards a well-guarded secret that we naively imagine we are constructing (discovering) through the film. Eluding the commonplace regime of causality, the fantastic uncovers (without necessarily putting it into images) our unthinkable, and surprises the fragility of the certainties that shape our desires and awareness, our helpless attachment to the excessive rationality that rules our world. And since the film has us take images for reality, fiction for what is possible, it uses this as a wicked spell to take us behind appearances.

The sole guide for this programme of eight films (including I Am Not a Witch) was the intention to capture through various films the different states of the fantastic. And rather than systematically insisting on the similarity of the works, it was the openings created by their juxtaposition that defined our choice. A way of asserting that the fantastic has different natures and that each one, to take another fitting phrase by Antonin Artaud, is “an effort towards true cinema”.

Jérôme Baron