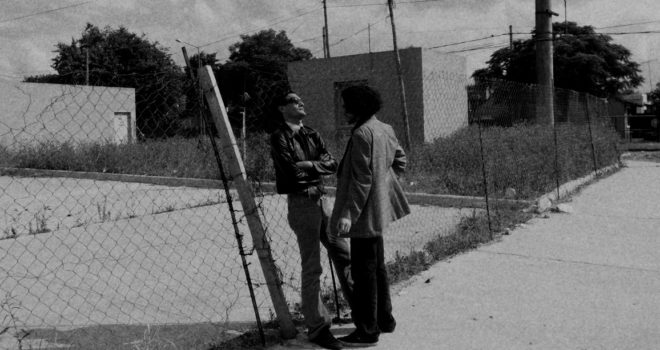

Sean eternxs by Raúl PERRONE © Trivial Media

For the past 30 years, and with nearly 60 films to his credit, Raúl Perrone has been a giant in Argentine cinema, albeit surprisingly on its fringe. Independent even of his country’s independent film scene, Perrone is bound exclusively through his life and his work to his birthplace of Ituzaingó (in Corrientes, an hour from Buenos Aires), which he only ever leaves for brief periods. He seeks neither fame nor recognition: he simply makes films. These can be compared to unpredictable subjective drawings as precise in their depiction of the reality of the people around him as they are open to the influence of unpredictable imaginary forces; and to conversing freely with other arts such as cinema itself, painting, and literature…

Editorial Raúl Perrone, The Straight Shooter from Ituzaingó

It is enough to move a few kilometers to the south or west of the city of Buenos Aires to verify that its surroundings, under the jurisdiction of the province and not of the Federal Capital, have little to do with the fantasy of locals (and foreigners) of Buenos Aires as a southern branch of Paris. In the suburbs, diverse populations agglomerate in various districts in which another Argentina is revealed.

Here we find the mystery and obstinance of Raúl Perrone, the greatest Argentine filmmaker of the last 30 years, and the only indisputably independent one: he has devoted himself to filming the place where he was born. His entire filmography is limited to Ituzaingó, a city in the province of Buenos Aires, located less than 30 kilometers from the capital, in which more than 160,000 inhabitants live. Perrone once filmed in another province, but he always focused on that territory, even when on occasions he transfigured the landscapes and buildings of his city into unknown jungles, European forests and rural areas of Japan. Having turned Ituzaingó into its own Cinecittà does not mean an unrestricted fidelity to portraying the city that shelters it. On several occasions, yes, but not always. The filmmaker has created beautiful portraits of the simple life of the poor people of Ituzaingó, but he has also imagined samurai, wild creatures from Africa and decadent Europeans, meters from his house. In a recently released film entitled Sinfonía, for example, he discovered that the great Argentine writer and filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky could be a reincarnation of the Marquis de Sade. Perrone’s imagination is an enigma. Where does his genius come from? Perrone has been filming since the late 1980s.

Not even he knows exactly how many movies he has made. More than sixty? Seventy? He once had financial help for the realization of some, but he has almost always worked alone, managing scarce material resources and maximizing the occurrences of his imagination. The technological evolution of the last two decades has allowed him to capture what he conceives, both awake and in dreams. He first started filming on video and then went through all the intermediate formats up to the present standardization of the digital image. Currently, Perrone is, along with Pedro Costa, the filmmaker who has best understood both the emancipatory power that nests in the digital record as well as the concomitant need to establish a dialogue between a new ontology of the image and the previous one. Indeed, the only way to establish continuity between the grain of an analog shot and the synthetic texture of a digital shot lies in recognizing a history of the frame and a laborious study of the path of natural light over the space chosen as the visual field.

That Perrone was a professional cartoonist for many years is not just another biographical fact. His eyes attend to the stimuli of the world without forgetting his hands. This tactile relationship has fully recovered them and transformed them into something different, taking charge, a decade ago, of the editing of his films. Perrone the editor outlines the shots that he gathers during the filming. In the exhaustive review of what he has filmed, the shots become something else. The paradox: Perrone’s assembly method is very manual. He does not use a moviola, but by using old machines he has invented an extemporaneous but efficient

relationship in his work in which he assembles the material filmed during the week.

BETWEEN TWO CENTURIES

Perrone’s films are never the same and they all look alike. What do Canadá, Late un corazón, La Mecha, Cínicos, 3scombro5 and Sean Eternxs have in common? What relationship can be established between Labios de churrasco and P3ND3JO5? First, the territory is the same: the streets of Ituzaingó, the central square, the train station, the small shops, the bars and the clubs, always interspersed with shots of the city’s clouds. Second, a tenuous but constant concept of community is repeated in all the stories. It is never about an isolated character, because the films never have solitary heroes. And something else, perhaps a non-negotiable obstinacy in his films: as the years go by, every two or three films, Perrone stops to film the lives of young people. The biography of the youth of the lower classes has in Perrone its best interpreter and portraitist.

The time that passes between Labios de churrasco and Sean Eternxs coincides with the same period in which cinema abandons its photographic material and adopts its digital ontology. That change is documented in Perrone’s cinema as in that of few other filmmakers. The young people of Labios belong to a less rushed and hostile time. Helplessness still does not define them; precariousness does, and there is still a limited but possible chance for obtaining some happiness. However, Las pibas announces and then confirms with P3ND3JO5 a different time and state of mind among youth, coinciding with the assumption of an aesthetic supported by digital cinema. That random conjunction resulted in a reinvention of the close-up of faces, and also a reconsideration of how a face was viewed in silent film, in light of a new age of the moving image.

But with P3ND3JO5 Perrone not only lavished on the close ups an aesthetic dignity haunted by the compulsion to take a selfie; he declared his radical emancipation. Without dispensing from time to time with the poetic realism of his films of the 1990s and the first decade of the current century, he decided to radicalize his formal system. Crossfades and overlays, narrative discontinuity or hyperbolic ellipsis took over the syntax of his films. The stories, more than seeming like dreams arranged in sequences, felt like stories built from dreams. Isn’t there something in the Perrone’s latest work that refers to the aesthetics of the earth of Glauber Rocha? Hierba, Corsario and Samuray-s can be seen as barely decipherable dreams in which Monet, Pasolini and Mizoguchi circulate like signs of the seething unconscious of a creator. Then comes the instance of montage, in which the anomaly of associations characteristic of the dream is respected, adding extremely complex sound layers that once again trigger a referential instability in the story. The result is magnificent, disconcerting and abysmal.

How can the Argentina’s most working class and experimental filmmaker remains ignored? It is time to study his work, ask what means this mystery for contemporary cinema and give it a space. In Nantes a path begins, in Nantes a bit of justice is dispensed.

Roger Koza

Critic and programmer