Yu Lik-wai: chimeras of the modern world and digital reality

Engaging in dialogue with Yu Lik-wai is to encounter the inseparable experiences of a film director and cinematographer. As both actor and witness of the cinema’s passage into a new digital reality, he has worked on films that accompany the transition of the vast Chinese world into a new age of social and economic change. When considering his own films and his long collaboration with Jia Zhang-ke and others, we had the impression that his work carried instances of an immediate cinematic reality that could be described, for want of a better term, as a unique “feeling” of reality or, should we say, a unique “sensation” of the real. If we refrain from looking at the (digital) images of contemporary cinema solely through the prism of what these have allegedly gained or lost, or what more or what less they possess, we can move closer to the experience of Yu Lik-wai’s filmmaking and observe the readjustment of fundamental ontological virtues in a context where the uncertainty of ongoing dissolution and mutation requires an unwavering power of seeing.

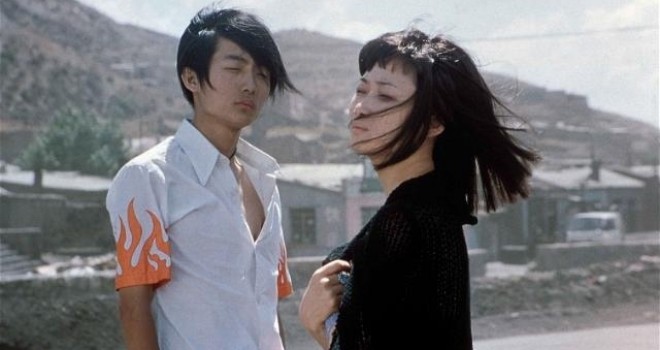

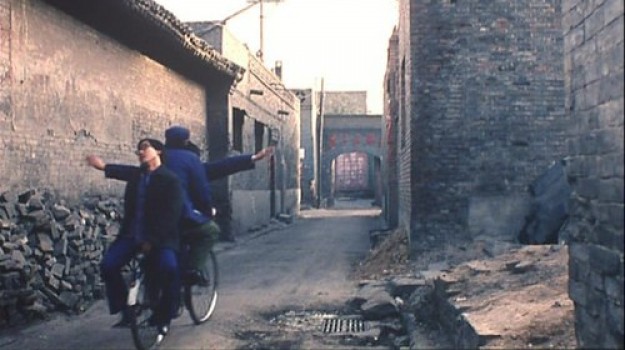

From clandestinity to the fringe… there is a close link between Jia Zhang-ke’s first film, on which Yu Lik-wai worked as cinematographer, and the film made two years later by Yu Lik-wai in Hong Kong. Not an aesthetic continuity from the first film to the second, but rather an affinity, a relationship of historicity that, in hindsight, seems to foreshadow – between these two men from the same generation – one of contemporary cinema’s most remarkable partnerships. Although they come from opposite ends of China, one from the North and one from the South, what Jia Zhang-ke and Yu Lik-wai have in common with Xiao Wu and Ah Jian, the characters from their first films, is that they have no place on the cinematic map, not even in the off-screen zone. They are absent. A clandestine statement for Jia Zhang-ke, an appearance on the fringe for Yu Lik-wai: in Xiao Wu artisan pickpocket and Love will tear us apart, like the later Platform and Unknown Pleasures, there flows the supreme ambition to film the march of History within the temporality of those experiencing it: migrants, vagrants, prostitutes, itinerant performers, displaced villagers, inactive workers, small-time crooks. A whole people of nobodies wandering through some inner exile occupy the frame. They are unwittingly condemned to journey through times that are gradually eluding the guidance of any deterministic conceptions. A people prepared by half a century of Communism and a long feudal history to endure a new regime of subjection brought on by the advent of State capitalism.

Whether working together or separately, the two directors seek to identify the breaking points, the fragmentation and the heterogeneity in the way that people live, including their deeply intimate experiences, when history is irreversibly on the move. Be it from a street corner, the back of a bus or a corner of wasteland, Jia Zhang-ke’s films seem determined to capture simultaneously, in the same shot, the transition between things as they were and an already completed transformation. This unavoidable tipping point is apprehended differently in All Tomorrow’s parties and Plastic city as Yu Lik-wai seems to have outpaced the turning point and already taken a post-disaster stance.

From Xiao Wu to Still life, from Love we till us apart to The World, there is a single explicit concern: the ongoing recomposition of the Chinese landscape induces a gradual dissolution of collective reference points and social norms that undermines even the family’s traditional unity and affects the very nature of desires and feelings. The more Jia Zhang-ke and Yu Lik-wai focus on the slippage of these references and on the alienating, morally diminishing loss of identity (disguise is a recurrent motif), the greater the irreducible distances between their characters. The massive agglomerations spawned by frenetic urbanisation are completing an increasingly intense process of devitalisation. The passage of time in the long takes, where the characters of Platform drift with the vague purpose of a movement that never comes, gives way to the glitzy and morbid sheen of modern beauty.

Unsurprisingly, Jia Zhang-k’s films, whether set in Beijing or elsewhere, contain multiple and even anecdotal references that recall his native Shanxi. As if he too feared that he might lose his roots and see his sensations, memories, imaginary pathways and cultural heritage fade away.

But the power of Jia Zhang-ke’s filmic statement does not rely on the lucid harshness of observation alone. It also hinges on the eye and technique combined: in other words, vision. And this would certainly never have taken the form we know, had Yu Lik-wai’s brilliant mastery of video tools (in China, those of underground resistance) not infused his images with new qualities. His photography, firmly anchored in reality, makes no concession to naturalist inclinations. What is more striking is the acuity of the attention he pays to things. As if the world were constantly using its subtle palette to create a hidden drawing, a document that cinema had to find ways of revealing in familiar but complex dimensions. With video, there have been frequent attempts to highlight similarities with celluloid film. Here, on the contrary, the flexibility of the tools and their sometimes trivial technical limitations pave the way for Yu Lik-wai’s pictorial searches, which offset a certain sobriety of the images, as in Unknown Pleasures. The documentary gesture is redolent of that of (outdoor) painting and, in other respects, that of traditional Chinese painting (Still life). Yu Lik-wai and Jia Zhang-ke’s world is already – even before they make their films – brimming with images, gifted with memory and deep impressions. It operates in a hidden way that is untimely but tangible. Their cinema conveys the present reality of a world of images criss-crossed by their contemporaries. Unaware, they move through this world. Perhaps for the last time. Cinema is there to capture this final moment that relentlessly asks the same question as if to better resist collapse: what position can one take with things and people so that their very presence constitutes an event? And Yu lik-wai offers some precious answers.

Jérôme Baron