Love stories in cinema often seem to follow a tirelessly repeated formula: love at first sight, declarations of love, painful separation, and eventual reunion, culminating in the expected happy ending. So why do we continue to adore them? Perhaps because we do not fall in love every day, and simply witnessing this emotion arise and be experienced by others – even on screen – reminds us of the desire to inhabit the very idea of romantic reality.

This thematic programme seeks to explore that desire by broadening the concept of love to encompass multiple forms of attachment – friendship, affection, tenderness – all of which create a sense of ‘us’ with others, from one continent to another.

Read the editorial

In cinema, love stories follow on one after another and, on the face of it, they are all much alike: an encounter, a thrill, a separation, a reunion. Yet, this formula, played out a thousand times, loses none of its evocative power. We know it by heart, yet each time it still manages to move us. Possibly because it reiterates the fundamental mystery of love, the quicksilver whose alchemy remains secret: an oscillation between obviousness and lack, between promise and loss.

If we still enjoy these stories, it is because they concentrate what life often dilutes: the intensity of a presence, a burning desire, the precious and fragile beauty of a bond.

But love, on screen and in life, is not limited to a lovers’ embrace. Love unfolds in countless singular forms that this thematic programme aims to explore: friendship, tenderness, solidarity, kinship. Myriad ways of inventing an “us” with others. The truth of this emotion lies in such plurality: loving means inhabiting the world through others, discovering in the other who we are not.

In Idrissa Ouedraogo’s Yaaba, deep in a village in Burkina Faso, two children strike up a friendship with an elderly woman shunned by her community. No romance between them, but a pure unwavering affection that defies prejudice. The film reminds us that love, before being passionate, implies recognition — seeing the other simply for what they are. This lesson in gentleness irrigates the narrative like the river where the children play, weaving words, gestures and a shared trust into the very fabric of human ties.

On the other side of the world, Jeong Jae-eun’s Take Care of My Cat portrays the friendship between five young Korean women on the threshold of adulthood. The animal in the title wanders among them like an invisible thread, the metaphor of an enduring bond despite the distances and changes of their unsettled lives. Here, love becomes sisterhood, listening, care. It is written into the silences, the messages exchanged, the absences filled by tenderness. The film says something about our times: loving sometimes means continuing to write, even when words no longer suffice.

In The Lunchbox, Ritesh Batra films the correspondence between two solitudes in Mumbai following a meal delivery mix-up. Love is a perfume, a taste, a silent attentiveness to the other without ever touching them. This is no romantic firestorm, rather the discreet embers of a bond born of chance and patience. What cinema teaches us here is that love is not always a dazzling blaze. It can also be the heart’s hospitality: an unexpected openness to a stranger in everyday life.

Saim Sadiq’s Joyland takes this exploration even further by filming the emergence of an illicit desire condemned by society. Here, love becomes an act of resistance: affirming the complexity of desire, the dignity of emotions, the right to exist differently. The film portrays a love that is both intimate and collective, full of shame, courage and a beacon of possibilities. It is a reminder that when filming love, cinema is also speaking about freedom of choice.

In Leyla Bouzid’s A Tale of Love and Desire, love becomes a lesson. On meeting a student girl from Tunis, a young French-Algerian man discovers a blend of sensuality and modesty from a cultural heritage unknown to him. Here, love means coming to terms with oneself: encountering an unknown language, extending a personal history into the present. The filmmaker reminds us that desire can lead to self-knowledge, a journey through life that is both sensual and spiritual.

Other films explore other dimensions of the question. Franco Lolli’s Litigante depicts the unconditional strength of a mother’s love — a love that protects, affronts and sometimes overflows. As for Maryam Goormaghtigh’s Before Summer Ends, the film follows three Iranian friends travelling around France before returning home. Their melancholic road trip turns into a meditation on friendship and the desire to belong. Love is not a passion between two people but a diffuse feeling, a human warmth circulating from one face to another.

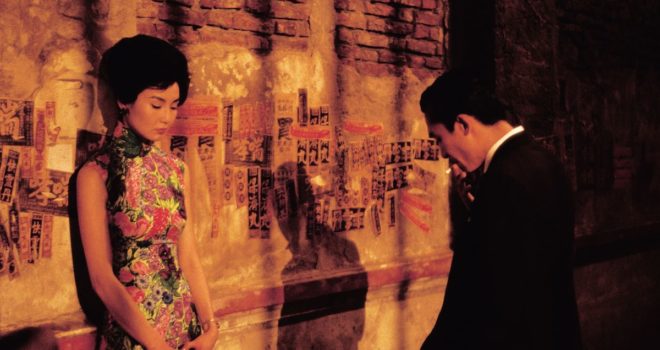

From Yaaba to Joyland, from The Lunchbox to Before Summer Ends, these films make up a sensitive map of love, crossing continents, ages and genders. They remind us that love is not so much a settled affair as a movement, sometimes even a light touch, as in In the mood for love: a tension between emptiness and plenitude, between reality and imagination.

In cinema, love is not an escape from the world. It invents or discovers a space for experimenting with this emotion, a reflection on ties. Cinema is not content with representing love: it explores its forms, rhythms, silences, using its substance to create an experience of sensibilities and intensities. The imprint left by a film can transcend the echo of a transient emotion and advance the possibility of a transformed gaze — an apprenticeship of presence, otherness. As the philosopher André Comte-Sponville wrote about love “We hope for only the possible, we live only reality”. And as usual, cinema doesn’t choose it wants it all –it wants to love.

Jérôme Baron