The festival explores Sri Lankan cinema through an exceptional programme of rare works, some of which have been restored, from one of South Asia’s least-known film industries. This retrospective stems from a collaboration launched in April with the National Film Corporation (NFC) and the Sri Lanka National Archives (SLNA), as part of the France–India–Sri Lanka Cine Heritage (FISCH) project, coinciding with the restoration of Sumitra Peries’ masterpiece The Girls (1978) by the Film Heritage Foundation.

Retrospective supported by the French Embassy in Sri Lanka.

Our most sincere thanks for their commitment to Sri Lanka National Archives (Dr. Nadeera Rupesinghe, director), National Film Cooperation (Mr. Sudath Mahaadivulwewa, Chairman), and to Lester James and Sumitra Peries Foundation (Ms. Gayathri Mustachi, Chairperson), Mr. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur (Film Heritage Foundation, India), Tee Pao Chew (Asian Film Archive, Singapore), Mr. Dammith Fonseka, Mr. Ravindra Guruge, Mr. Prasanna Vithanage, Mr. Chamath Edirisuriya, Mr. Milanda Pathiraja, Mr. Haren Nagodavithana. And for their kind advice : Mrs. Hiranya Perera, Mr. Ilango Ram, Mr Vimukthi Jayasunadara, Ms. Umali Thilakaratne, Mr. Ashley Ratnavibhushana.

Read the editorial

From the 1960s to 1980s, Sri-Lankan cinema could be viewed as the construction of an island memory: a mirror held up to a changing society that swings between a cumbersome heritage and expectations, isolation and the desire for change typical of a post-colonial society. On this island swept by the winds of history, filmmakers from the golden age — Lester James Peries, Sumitra Peries, Dharmasena Pathiraja, D. B. Nihalsinghe, H. D. Premaratne and Titus Thotawatte among others — invented the possibilities of a gaze commensurate with their territory: sensitive, fragile, critical, firmly rooted.

Their cinema emerged in Sri Lanka in a cash-strapped economy, but this precarity is what spawned its beauty. Filming there meant filming what is close, albeit kept on a far-flung edge of the world. So how was it possible to create and lend substance to the representations and narratives of a society until then invisible? Their films recount modest lives, the slow disintegration of a social order, the collision between immobile villages and an urban modernity gnawing away at certitudes, the diffuse shadow of a colonial legacy that has left tangible and sometimes profound traces. They are stories of water and earth, rain, rice paddies, where man seems to be constantly searching for his place without ever having known another.

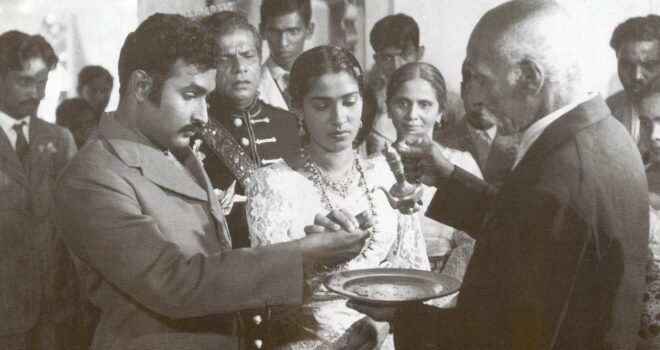

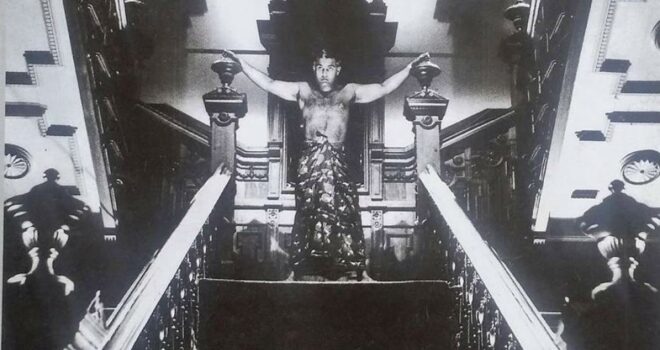

The guiding light of Lester James Peries gave the country its first cinematographic ambitions. From The Line of Destiny (1956) to Changes in the Village (1963), from The Treasure (1972) to The Village in the Jungle (1979) and many other equally essential works, he successfully captured the painful spasms of a rural world and a disappearing aristocracy. His gentle and vigilant mise en scène espouses the rhythms of lives often attached to illusions and measures the weight of complex interactions without disregarding any. With him, Sri Lankan cinema found its unique founding path, the notion of the frame as a space where present and past co-exist inseparably. His is a legacy that will remain forever prodigious.

Originally a film editor, his accomplice and wife, Sumitra Peries, continued this movement with her own inner feminine sensitivity. Among her ten feature films, her first film, The Girls (1978), and A Letter Written on the Sand (1985) portray women’s destiny as a place for exploring change: how to love, how to exist in a society still governed by convention, by the realities of social class and patriarchy? In her work, faces become the mirror of an island that is awakening, torn between a costly integrity and a desire for emancipation.

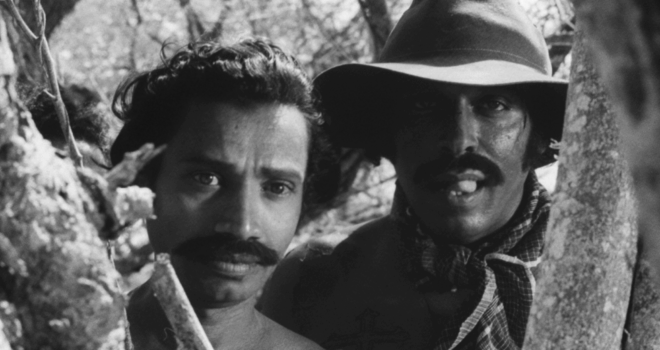

With Welikathara (D. B. Nihalsinghe, 1971), the first South-Asian film shot in CinemaScope (black and white), local filmmaking was experimenting with an ambitious format that well served a razor-sharp gaze. Shot on the Point Pedro sand dunes on Jaffna Peninsula, the film plays on contrast: the widened frame does not increase the film’s monumentality but rather accentuates the distance between people, bores into margins and spaces to better highlight the protagonists’ growing isolation. Behind the mechanism of a crime thriller — the confrontation between a police chief and a local gang leader — Nihalsinghe lays bare the fragility of institutions and the tension of a territory experiencing profound social change. CinemaScope becomes a critical tool: rather than opening up a triumphant horizon, it brings back the clouds of the past, returns the characters to their alienation in order to more clearly reveal the latent violence that causes any notion of order and control to teeter.

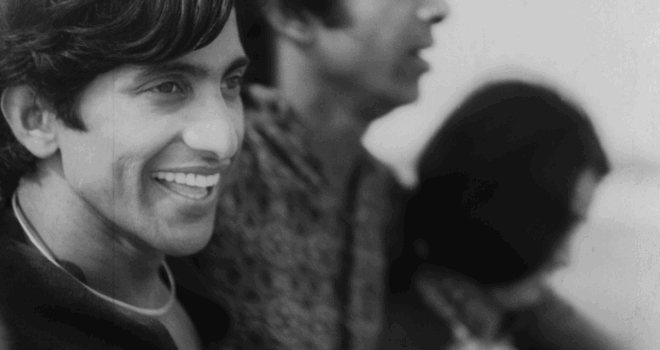

In the 1970s, Dharmasena Pathiraja opened a further breach that was lucid and troubling. Nourished by politics and poetry, his filmmaking views the country as a fractured terrain. In One League of Sky (1974), he films a disoriented urban youth left to their dreams, the powerlessness of their rebellion and their sentimental dilemmas. The tone is already one of disenchantment: the world is changing, and the promises of emancipation are frittering away. In The Wasps Are Here (1978), Pathiraja attains a remarkable intensity. The clash between traditional fishermen and young entrepreneurs keen to impose their market logic becomes the parable for a country on the brink of transformation. The shore, a place of work and desire, represents the whole island – a closed space, besieged by forces from elsewhere. Harsh and luminous, the film portrays a people fighting to prevent their own disappearance. Pathiraja transforms social commentary into an elegy: the sea is both promise and threat, frontier and abyss.

This attention to the fissures and to shifts of viewpoint also runs through the works of Titus Thotawatte and H. D. Premaratne, two filmmakers who never opposed a political approach and a personal sphere. In Handaya (1979), Thotawatte was keen to make a popular film (still popular today) and for his vantage point he chose childhood. In a village undergoing change, he observes a group of children left to their own devices and captures the early emergence of an awareness of both solidarity and disillusionment. With great formal clarity, the film records the awakening of a viewpoint — that of a generation facing the loss of a world whose landmarks it already no longer recognises.

With The City (1995), Premaratne pursues this exploration at a time when disillusionment had already become deep-rooted. The film reveals, without being didactic, the disintegration of a rural world undermined by corruption, economic domination and disenchantment. Through the fate of a couple caught in a spiral of dependence and betrayal, Premaratne unpacks the compromises imposed by survival when moral bearings falter. His relentless realism depicts the slow corrosion of values and emotions, the symptom of a society that blindly trundles through its own narratives.

Each of these films in their own different way reject nostalgia as much as disavowal: they question what becomes of a community when it no longer recognises what it sees. Invisible, always off-screen, never named, the civil war that tore Sri Lanka apart for some thirty years (1983-2009) seems to operate subterraneously, as a latent backdrop, inoculated, undergirding the narratives yet never openly stated.

Certain on-screen faces have played a key role in consolidating this cinema. Gamini Fonseka, Joe Abeywickrama, Swarna Mallawarachchi, Malini Fonseka or Cyril Wickramage, among others, often feature in the films as emotional landmarks, bearers of a shared memory. Each of their appearances recalls the one before, linking together disconnected stories, as if Sri Lankan cinema and the country were using them to tell their story, faithful to those to whom they had given a face: a way of inhabiting the world without ever dominating it.

In this landscape, Prasanna Vithanage appears as an heir uneasily following in their footsteps. Reprising the figure of Malini Fonseka in Flowers of the Sky (2008), he is not simply paying tribute to a national icon. He is questioning the destiny of Sri Lankan cinema itself. Fonseka, in the role of a forgotten actress, becomes the incarnation of an art threatened by oblivion, or a county in the grip of amnesia. This overwhelmingly unassuming film confronts the beauty of images with their deletion: what was filmed, what can still be saved. Vithanage’s gesture is in no way commemorative: it is an ex-ante gaze, in the present, that of a filmmaker aware of the disappearance of the forms and bodies that shaped his horizon. With the utmost restraint, the film questions cinema as a place of survival – a place where the visible becomes memory, and where loyalty takes on the form of a final shot. The film is also included in this programme to pay sincere tribute to someone who came to be known as “the Queen of Sri Lankan cinema” and who passed away last May.

From the Peries couple to Pathiraja, from Gamini Fonseka to Prasanna Vithanage, and their successors, Sri Lankan cinema has invented, loved and resisted its own geography. An island cinema, yes — but one whose reach, through its precision and melancholy, attains a universal dimension: the fragile beauty of existing, that of an island that looks at itself to understand the world.

Jérôme Baron