A major figure in Taiwanese and international cinema, multi-award winner and two-time recipient of the Oscar for Best Director, Ang Lee will be honoured with a presentation of his filmography.

From Pushing Hands (1991) to Gemini Man (2019), via The Wedding Banquet (1993), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Brokeback Mountain (2005), this complete retrospective will allow viewers to grasp the threads of a body of work that is unpredictable in its trajectory and innovative in its approach to film genres. These feature films tackle themes of intimacy, identity and social constraints, uprooting and parentage.

Retrospective supported by the Taiwan Cultural Centre in Paris and the Taiwanese Ministry of Culture.

Read the editorial

From Taiwan to Hollywood, Ang Lee has never stopped moving around — between languages, genres, traditions, technologies. Nothing in his work relates to conquest: it is rather movement itself – in his own words, zigzagging – that constitutes his oeuvre. His cinema is invented in crossings, on fault lines or at intersections, where modern world tensions are played out — between fidelity and rupture, emotion and reflection, having roots and displacement.

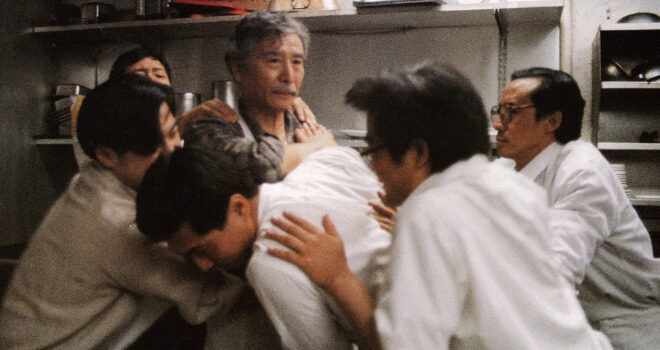

Born in Pingtung, trained in Taiwan and the United States, Ang Lee belongs to the generation for whom cosmopolitanism is not a subject but a fact. His gaze is that of a filmmaker of the in-between, of comings and goings: attentive, never really close, never there where we expect him. He turns these shifts into the very substance of his art. His first three films — Pushing Hands, The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman —are sometimes dubbed the “father trilogy”, but rather than form a series, they provide a throughline focused on ties, transmission, the tension between generations. Behind domestic bliss and situational irony, Lee films a world in translation: the world of a culture split between duty (Confucian) and Western individualism, between memory and transformation.

This intimate theatre is also an aesthetics laboratory. Alongside James Schamus, his accomplice and screenwriter for twenty years, Lee forges a style of writing that displays a rare precision: underneath its apparent limpidity lies a subtle moral and poetic architecture where each gesture has its weight and at times a symbolic value. The complicity between the two men gives Ang Lee’s cinema a special chemistry: it is both popular and contemplative, accessible and stretched towards the abyss.

This tension between surface and depth runs through all his work. Sense and Sensibility transposes the same questions to the England of Jane Austen: economy governs the emotions, and modesty becomes a form of resistance. The Ice Storm tweaks the terms of the equation to turn its gaze towards 1970s America: under the illusion of a freedom regained lies the erosion of a collective bond. Ride with the Devil projects civil war as the collapse of meaning: causes are erased, leaving nothing but the moral disorder of a country without bearings.

Yet, it is with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon that Lee conquers a new space – that of the myth. Revisiting the wu xia pian (martial arts film), what he creates is not martial arts entertainment but a poem of movement (of hearts). Bodies defy gravity to embody the fundamental dream of cinema: that of suspending reality. Behind the choreographic beauty of the fights (which unfold like actual thoughts) there is a rising sense of nostalgia for an ancient order where honour, loyalty and desire join together in the same tragic destiny.

Brokeback Mountain reverses the gesture. Here, the freedom of vast spaces becomes the frame of an inner imprisonment. Reinventing the Western, Lee films feelings as a dissonance — what cannot be said but continues to be. Behind the modest gestures, a dull cry, behind the light, the silence of a society.

With Lust, Caution, adapted from Eileen Chang, the return to the Chinese world spells a spate of adversity. The film takes up the tensions found in the novel: seduction and domination, desire and politics. Everything is ambiguous, unstable: bodies, spoken words, the mise en scène. Lee questions the very power of cinema and its capacity to conflate truth and representation.

Then comes a swing to the experimental: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, Gemini Man, where technology becomes metaphor. High frequency images, the duplication of the body (the body had already metamorphosed into its mutant double in the magnificent Hulk, which unfortunately we cannot screen) and the virtual world all challenge human presence. What remains of flesh when the image reproduces it better than itself? These experiments pursue an ancient quest: the search for a gaze keen to address reality without fetishising it, the search for a singular emotion where spectacle is not an end in itself but the condition.

Between these poles, Life of Pi appears as a secret centre. As a film about belief, it condenses Lee’s entire project – namely, to explore the limits of the visible and experience fiction as a form of truth. In this crossing of existences, the tiger and the child are not opponents — they coexist, as do dreams and reason.

From Taking Woodstock to Sense and Sensibility, from the digital world of Gemini Man to the updated classicism of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the same line is drawn: the line of a cinema of distance — not a withdrawal, but a fertile tension between the gaze and the world. For Ang Lee, distance never signifies coldness, rather a space for listening, for resonances, where contradictions can coexist without being resolved. It becomes the precondition for the truth of emotions, a fragile terrain where the intimate can meet history, where passion confronts restraint, where a technical gesture becomes thought. It is in these gaps that his cinema breathes, measures the share of unknowns that separate beings, and even transforms this separation into the very place where their communion is possible. Whether filming the kitchen of a Taiwanese flat or the clarity of a digital ocean, Lee captures the tension between order and confusion, heritage and transformation. His characters never really settle down: they wander between cultures, in their own times, between forms and their sometimes-confused desire. When bearings disappear, they then have to reinvent a way of inhabiting the world. For this reason, Ang Lee’s films shun closed affiliations (for instance, the divide between belonging and uprooting, between transparency and opacity), and cross genres to test their plasticity.

Fluid and uneasy, his cinema tracks the reality of a shifting truth, and there remains this rare space where the gaps are not filled — they come alive, play out repeatedly, refract with each encounter.

Jérôme Baron