Any history of cinema proposed would be neither true nor false. It would be incomplete, always partial, sometimes idiosyncratic, seldom fair. Something would always be missing: a name, an event, a debate, a dissent, a title. So we agree that in this so-called “real history of Argentine cinema” some indispensable films and authors are missing. These absences have an explanation. Paradoxically, the reasons for any exclusion clarify the reasons for what is included. Is this logic really so strange? Here, the paradox lies in the off-screen dimension of the selection: the missing films can be sensed from those that are included.

A priori, all kinds of obstacles stand in the way of the specific request to “write” a history of Argentine cinema in films. The first hurdle is a material one: the institutional precariousness of Argentine cinema. The country has no national film library that we can count on; there is and never has been any government policy that could have spawned an institution bringing together all of Argentina’s film output. This explains, but not completely, the absence of a film from the silent movie era. There are copies that have recently been recovered and restored by private individuals, films of undeniable interest. But, this is little far from the initial request that I received from Jérôme Baron, who suggested I make a choice that would show the link between the art of cinema – in all its forms, from the most popular to the most marginal – and its time, sometimes even its link with the politics and the history of my country.

And then another hurdle appears: not all films establish a close relationship with their time, even though the present of their making always ends up peeping through in the mise-en-scène. Cinematographic ontology itself invokes their present, without however symbolically inscribing every representation within a specific period. This explains the disappointing absence of a seminal filmmaker: Lisandro Alonso. A real history of Argentine cinema, even though it would be false, cannot allow itself to leave aside the work of Alonso. Yet the political dimension of his films hangs on small details or on the author’s obstinacy to remain faithful to an aesthetic that goes against the tide of entertainment cinema. In other words, Alonso’s conspicuous formalism has marked consequences for its reception. We could thus consider it to have an intrinsic political quality, because as it acts on the spectators’ sensitivity and questions their perceptions, it somehow helps to free them from the habitual procedures, even from the excesses of mainstream cinema, that have contaminated the productions of the prodigious giant of cinema. Seen from this angle, it is a political question of the highest importance. The same reasoning could be applied to the films of Gustavo Fontán, another key author in contemporary Argentine cinema that Europeans have only begun to discover over the last ten years. Jérôme Baron’s request, however, as no ambiguity.

Read more

Some noteworthy absences could be mentioned: Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, Manuel Antín, Hugo Santiago, Pino Solanas, Alejandro Agresti, Fabián Bielinsky, Pablo Trapero, Mariano Llinás, Matías Piñeiro, Celina Murga, among others. The overall rule that I followed was the following: avoid directors already well-known in France, whose films have been widely screened either in festivals or arthouse cinemas, and set aside films that belong uncritically to the cinematographic canon of Argentine cinema, often showcased in large festivals. We therefore leave Wild Tales to Cannes, whose disrespectful policy towards authors this year led to the rejection of Zama, the best Argentine film of this century, a prodigious anomaly that does not coincide with the reactionary poetics so dear to those in charge and which they defend in this increasingly conservative festival.

Among the above-mentioned authors, we should cite Bielinsky, whose absence mars this selection and still today seems to me irreparable. Nine Queens and El aura are essential films in this history – as they would be in any history – but a choice had to be made and other less well-known films (La Mecha and Pin Boy), along with a pivotal film (La Ciénaga), finally stood as inescapable choices for the period corresponding to this millennium. This choice revealed another ghostly presence: none of the films of this period feature Ricardo Darín in the lead role.

Llinás is another essential filmmaker but as in Alonso’s case, his films – be it Balnearios or Historias Extraordinarias (already shown at Nantes) – depart from Jérôme Baron’s explicit request: the cultural critique of the first and the endless adventure of the second do not express much about the age in which they were made. And yet, Llinás is (very) present: he is in fact the screenwriter and actor in one of the chosen films, The Gold Bug by Alejo Moguillansky. The absence of any of Llinás’ films is thus conjured by the presence of this other film, which bears his mark and spirit of revolt.

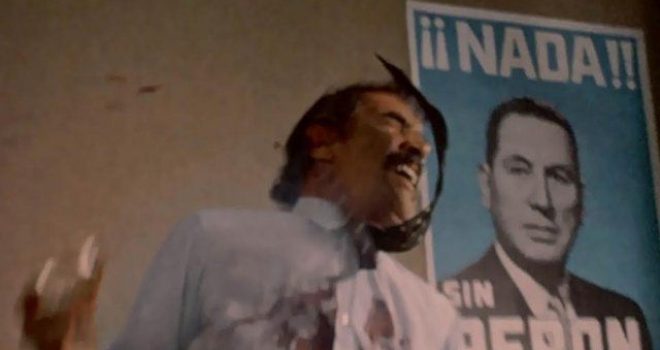

So what history is being presented to you here. A roundabout history. A detour that leaves the beaten path, and along which you can find singular works that remain on the verge or off the map (absent from the discussion). One good illustration: to evoke the most recent civil and military dictatorship, an Argentine filmgoer wanting to convey the terror through a filmic representation would cite La historia oficial; our choice would be to refer to Juan, como si nada hubiera sucedido (or Habeas Corpus). On the question of job insecurity towards the close of the millennium, Mundo grúa would be mentioned with pride; we, however, would name, not without an affable impertinence, Parapalos. The paths of the proposed history are side-roads. On the margin, at a some distance from canonical certainties, signs light up a journey and a history. In other words, in this proposal a complementary history of Argentine cinema can be read (watched and listened to).

Another reading of this twenty-two-film selection would be to view almost all of the films made in Argentina through a spatial logic. The films produced in the South, characterised by a peripheral heterogeneity based on another framework of references, another order of priorities, and also in production conditions vastly different from those of the films born in the heart of the central cinematographies.

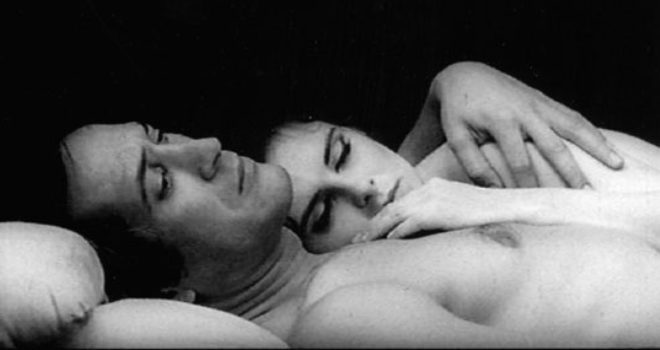

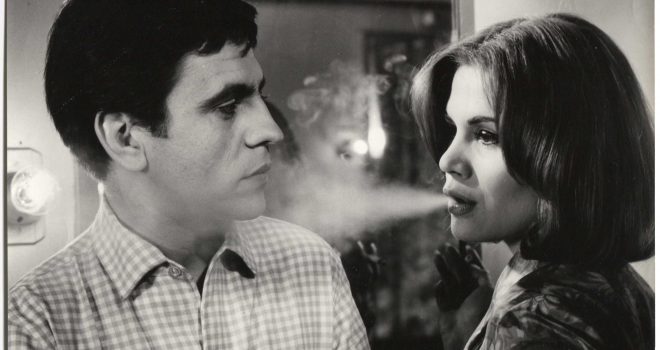

In this sense, the glory of classical Argentine cinema, and of the stars it brought to fame, are resplendent in The Law They Forgot, Don’t ever open that door and Amorina. A film such as La guerra gaucha, enables us to appreciate the intersections between a codified genre like the western – reprised here in the context of a historical experience that reproduces the founding gesture of a nation and the search for an further representation – and the singular thrusts that cannot be assimilated into the typical film of the American West. El romance del Aniceto y la Francisca, Pajarito Gómez and Brief Heaven are inconceivable without neorealism and the New Wave, but at the same time, they are decidedly different from their precursors. Similar remarks could be made about the experimental and avant-garde character of films such as Puntos suspensivos, Fatherland and Cuatreros. One could even evoke, depending on the case, the cinema of Makavejev, the Straub-Huillet or Godard, but, at some point, a detour, a divergence or even a betrayal of their authority comes into play.

The tradition of Argentine cinema stands out for its receptivity to inherited forms and its practice of a kind of assimilation, most often disobedient, which gives rise to sometimes invaluable innovations with respect to the origins. Argentine cinema has never produced a genre, as has Japanese or Indian cinema; let’s say rather that its filmmakers have more or less consciously explored the rules of composition and systems of representation that exist in the framework of a novel practice that departs from the established codes. To sum up, I will use a typically “French” term: the Argentine filmmaker “deterritorialises” foreign signs in order to arrange them in a new order of his own making.

This history is hardly an outline of a great history of Argentine cinema. It is a history that can open up other histories and the discovery of little-known authors. And unquestionably, the films presented will from now on be part of the cinephile’s history for the audiences of an extraordinary festival. And should a spectator, on seeing one of these films, feel that he or she wants to see other Argentine films, the mission of this selection will have been accomplished.

Roger Koza