In 1934, marking the ascendancy of the Portuguese dictatorship, a large-scale colonial exhibition was organised in Porto. To rival the other European empires, a map highlighted Portugal’s ambition to extend beyond its narrow rectangle of territory bordering the Atlantic. This ideological representation drew its legitimacy from the nation’s maritime discoveries and their mythological dimension. By adding its colonies to the mainland territory, the Empire reached an area equivalent to the size of Europe. At the bottom of the map was the following caption: “Portugal não é um país pequeno”, Portugal is not a small country.

Yesterday just as today, European ambitions have helped to shape a Western imperial imaginary and the national political fictions imposed on others. At a time when economic globalisation is causing disparate, asynchronous and accelerating change, to the point of repolarising geopolitical balances, we conjectured at last year’s Tricontinental Conference programme that one reason for Europe’s difficulty in effectively re-examining its situation stems from its persistent inability to break with its hegemony or the idea of a world where decolonisation is only surface deep. Our blinkers thus prevent us from a true rereading of history and from integrating the new perspectives that current reality inexorably imposes. While the cultures of once colonised countries remain affected by the workings of imperialism even today, we continue to pretend, in the name of a seemly or idealised notion of multiculturalism, that the differences that make us who we are today are primarily the result of this unresolved story. But too few stories are exchanged, and ever fewer shared or co-authored. No, the rupture with the past is not consummated. Our news misses no opportunity to remind us of that. And our epoch continues in different ways to harbour unequal and inegalitarian balances of power when it comes to cultural representation within the modern world order.

This programme confronts the reality of a complex legacy that is given no rest by the films presented.

Read more

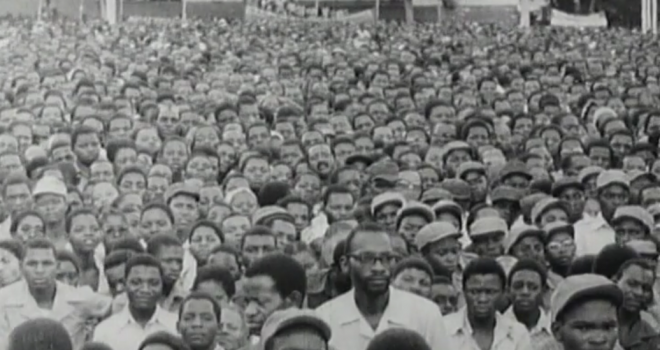

On 25 April 1974, Europe’s longest authoritarian regime was overturned by a military-led coup, dubbed the Carnation Revolution and coordinated by the Armed Forces Movement. This had originally started as a corporatist protest to defend the status of career officers against a law restricting the promotion of various ranks. At the helm since 1933, the Estado Novo government had introduced a single party (National Union) specifically tailored for the nation’s hegemonic strongman, António de Oliveira Salazar. He was removed from power in 1968 after suffering a stroke, and replaced by Marcelo Caetano. At this point, Portugal had been mired down since 1961 on several fronts of its endless colonial wars in Africa. The country was in the midst of recession and had thrown a good part of its vital resources into the conflicts which aimed, against all reason, at maintaining the proud integrity of the Empire. The war effort had devoured up to half of the state budget, while six percent of the country’s active population had been drafted into the army. During the two years of the large and chaotic revolutionary project that followed the regime’s downfall, the belated process of decolonisation was given a kick-start. The fighting was halted and the so-called african Overseas provinces were given their independence: Mozambique (June 1975), Guinea-Bissau (1973 but recognised by Portugal in September 1974), Cape-Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe (July 1975), Angola (November 1975). The end of the colonial wars and the declarations of independence also meant the return of over 500,000 nationals, (pejoratively) dubbed retornados, to mainland Portugal, whose population then numbered some nine million inhabitants.

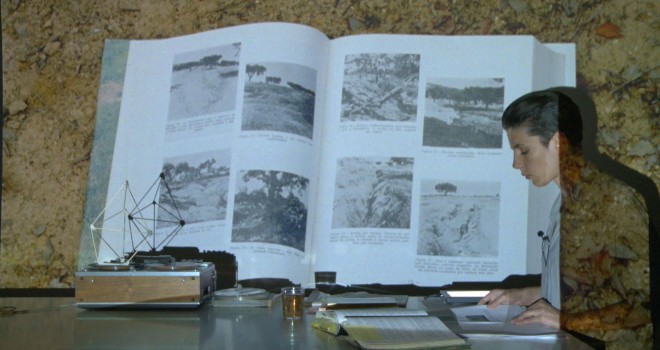

In this context, what role(s) was (were) to be assigned to cinema, both on the Portuguese side, and the African side, where it had thus far been inexistent? In our view, the case of post-revolutionary Portuguese cinema seems to be a singularity whose ramifications have spread out and lastingly influenced national film creation. The 1960s saw the beginning of a transformation in which a real artistic identity makes itself felt, despite the film industry’s particular situation (e.g. its isolation). This relates above all to a generational reality and the ambitions for renewal that permeate many cinematographies, from France to Brazil, from Cuba to Japan, and part of Eastern Europe. The gradual return of the veteran Manoel de Oliveira to regular filmmaking (he was 55 when he shot Rite of Spring in 1963) and the early films of Paulo Rocha, Fernando Lopes, António Campos, João César Monteiro, António Reis, António-Pedro Vasconcelos, and António da Cunha Telles all show that, as of 1974, Portuguese cinema was eager to participate in the country’s much needed cultural renewal. The Anos de Abril (Years of April), to take the title of José de Mato-Cruz’s book on post-revolutionary cinema, persisted well beyond 1974 and Portuguese cinema showed a perseverance and inventiveness in the multiple avenues it proposed to explore the questioning of the nation. When the revolution overturned Salazar’s idea of Portugal, this questioning (historical, anthropological, imaginary, poetic) was doubly emancipated and revivified. The artistic vitality of Portuguese cinema stems to a large extent from the pursuit of this questioning and, thus, from the open and implicit affiliations – unburdened by paternalism or cumbersome debts – between successive generations of Portuguese filmmakers and artists. Inevitably, this verve finds in the colonial past, and in the exploration of Portugal’s current relationship with Africa(1) (mainly), a field for reflection that has been revived with unprecedented energy over the past ten years or so. We consider that some œuvres have a pivotal and stimulating role, including the intermediate(2) films (starting with Down to Earth) of Pedro Costa, who eschews the temptation to play at leader. Yet, as always in Portuguese cinema, there are as many singular voices as there are filmmakers.

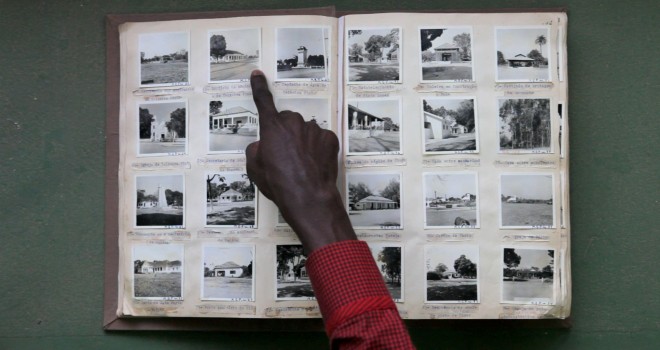

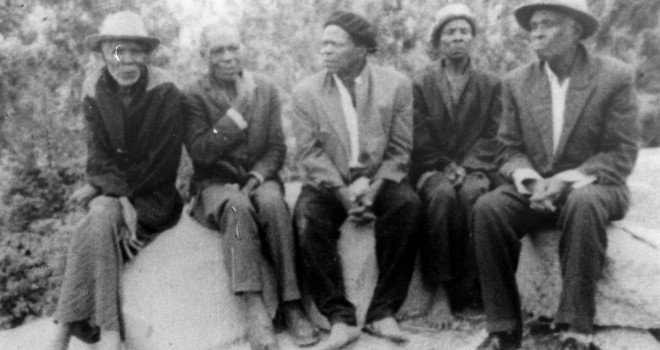

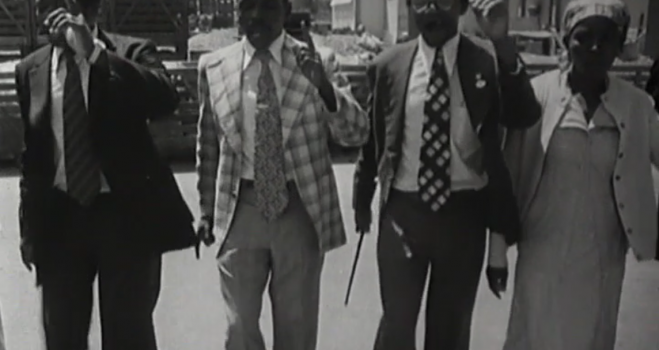

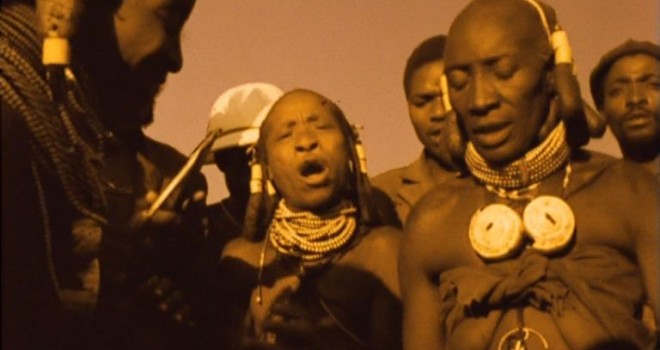

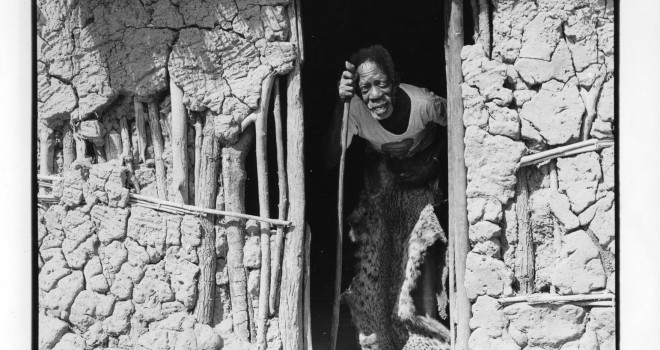

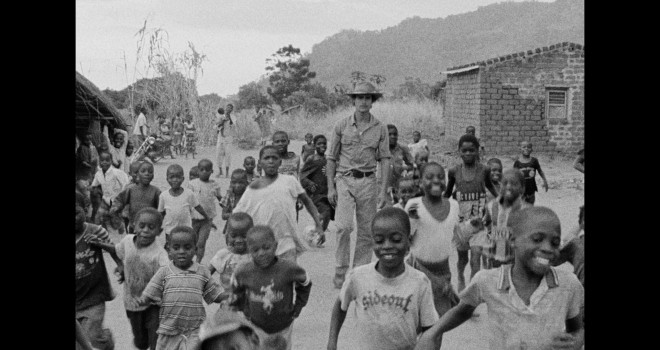

The importance given here to the singular situation of Portuguese cinema should not overshadow – quite the opposite – the importance of the cinematographic achievement in the African countries that regained their independence. We feel that it is pertinent and essential to juxtapose the examination of national conscience undertaken by Portuguese filmmakers and the emergence of a role for cinema in Angola and Mozambique in their respective revolutionary contexts. Several characteristics of these films heighten our awareness of the “births of images” in countries with no history of cinema. A first observation is that documentaries are in the majority and that, among these, we can distinguish two main complementary and overlapping trends. On the one hand, the immediate use of cinema as a place of remembrance and celebration. The traumas caused by the colonial rule are linked with the experience of the independence struggle, then with the celebration of victory. The need for catharsis is filled by forging a national narrative and, by extension, a federating and liberating mythology. Other films reveal the more ethnographic aim of addressing ethnic diversity and the heterogeneous cultural expressions and forms of social organisation in the different regions. A kind of mapping but also a discovery that seek to create images that are complex and a source of excitement in themselves. These two main trends visible in the films continue and contribute to the liberation process and to giving the country back to its people. Supported by the charismatic leaders of the freedom movements and the first presidents of the young People’s Republics (Samora Machel in Mozambique, Agostinho Neto in Angola), the production of these ambitious films came to an end in the mid-1980s with the outbreak of the fratricidal civil wars that were to thwart new-born hopes.

Little known, these cinematographies form one of the most important chapters in the history of African cinemas. They were even to encounter one of the rare fleeting moments of convergence between innovative European perceptions (Rouch and Godard travel to Mozambique to make their unfruitful but notable contribution) or Latin-American perceptions (Ruy Guerra, born in Mozambique, returns from Brazil, Cuba’s ICAIC trains Mozambican technicians and film directors) and the utopian desire to create the conditions for an experiment that would create an educational, home-grown and independent cinema.

Most probably, this programme only exists because we are still living in the shadows or subconscious of a colonial imaginary. It may simply be because there is still so much that we need to understand in order to grasp our present and build our future, or fill the abysmal void between generations. It may simply be because we are convinced that identities are something invented and that the human structures of our European societies are forcing us to rethink who we are and, as in a film, to reconstruct their reality by a fresh questioning of our colonial past. Far from claiming to be exhaustive, we have aimed with the chronology set out here to put the evolution of this questioning back to back with the questions of film aesthetics, and to establish a personal relationship with a memory separated from its collective dimension and freed from the limitations of national political representations. Here, historical decisions are taken, views are exchanged, filming and thinking are as one, stories are forged for the future, and what prevails is a freedom of movement and being, here or elsewhere.

Aisha Rahim & Jérôme Baron

Notes

(1) For example, the recent unprecedented situation, already blocked by falling oil prices, of a large wave of Portuguese economic migrants to Angola.

(2) In the sense that, in terms of generation, he is between the generation of April filmmakers and today’s generation.