The opening of Maya Darpan (1972), Kumar Shahani’s first film and one that revealed him as a filmmaker of the “parallel cinema” as it was then called, is enlightening. Over the scrolling credits, the sounds of a train, as if the film were leading us blindfold towards the place where it begins, to its cinematic expression. In some way, a Lumière shot from another age; the cinema has existed for half a century but it still has a long way to go, territories to explore. And it still has at least as much to do to confront the inordinate size of an India whose fledgling independence is grounded in social and spiritual structures that are as changing as they are distant and deep-rooted. In a series of varyingly scaled tracking shots accompanied by the voice of a woman singing, the train takes us into the labyrinth of a vast haveli, beautiful and dilapidated. Here, we soon discover Taran, the young lady of the house, wandering around her own domain, unlamenting. Clearly she is at home, but like a stranger, waiting. She strolls around, wordless. And the closer we get to her, the better we are able to measure what is refused her, as in a sort of suspended time where emotion makes its bed.

It has been written or said that Kumar Shahani’s films – like those of some of his contemporaries such as Mani Kaul (to whom we paid tribute in 2011) or Shyam Benegal – are obscure, inaccessible and formally influenced by European cinemas. Kumar Shahani has left himself more open to this criticism as he studied in France and assisted Robert Bresson on A Gentle Woman (1968). He was also a student of Ritwik Ghatak, who as we know distanced himself from what was ordinary in popular Indian cinema, although it was in fact the Indian people who formed the subject and central question of his poetic and iconoclastic work, to which each film made a unique contribution as if to strengthen the cinema’s vitality. The reservations expressed about Kumar Shahani at least recognise the novelty brought by Maya Darpan, its unexpected arrival – like that of his following films – on the landscape of Indian cinema. His films seek above all to counteract a cinema whose sole purpose would be to entertain, without however denying its dimension as spectacle in the sense of a singular experience.

Read more

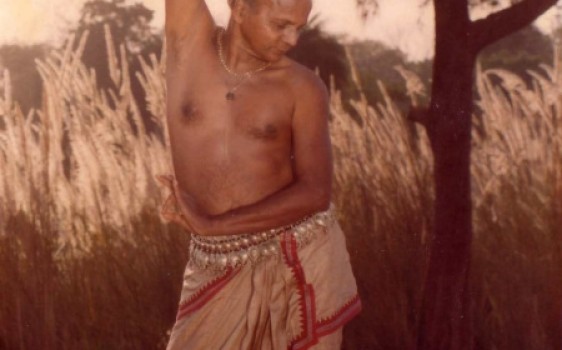

We usually think of modernity as being at odds with tradition and, in art, we see it as interrupting a classical regime of representation. Yet, when it comes to the great modern films in the history of cinema (Godard, Straub-Huillet, Syberberg, Pasolini, Oliveira… and mid-way, before these, Bresson, Rossellini or the last films of Dreyer) we are tempted to say the exact opposite. Kumar Shahani’s work offers us a perfect opportunity to highlight the way in which modernity welcomes and reconnects with the old order that is never quite past – in India more visibly than elsewhere – so as to re-arrange it and question present lives, permanent virtualities and founding beauties. This is also true of the essential relationship between his filmmaking and other art forms: dance (Bhavantarana, 1991), song (Khayal Gatha, 1989) and music (Bamboo Flute, 2000). Music, song and dance, as we know, all play a prominent role in Indian cinema. They are present in the developments of commercial cinema as the hallmark of a federating cultural and social tradition, but they also convey the continual toing-and-froing between the expectations of a modern India and its mythological foundations. In Kumar Shahani’s films, it is less a question of ingesting and assimilating these art forms – although Indian cinema does this masterfully – than discovering the points of intersection between the filmmaker’s medium and practices that have their own history and aesthetics. An aesthetic of encounter perhaps, of the contact between them? Yes, in a way. But it is above all a minimal theoretical intention to explore, via filmic means, the transcendence of an emotion that exists before the act of filming. How can dance be filmed? What happens when it is filmed? What do we see? And what do we feel? What do we hear from the film that passes through us and attests to the presence of a musician and the sound his instrument produces? Where does this sound really come from? What story does it tell us? The encounter is thus also a confrontation at times, it takes different twists and turns, and the film is the trace of this experience, a journey that plays out at the intersections between two worlds. We need to abandon ourselves to these experiences, which are spectacles in the strongest sense of the term, since they most often call on the senses rather than the mind. And on this point, there is certainly a basic misunderstanding of the aim of Kumar Shahani’s filmmaking, which distinguishes between form and thought without ever opposing or heirarchising the two. In fact, it is tempting to see this preoccupation as one he that shares with Ghatak.

The circularity of Kumar Shahani’s films, his repetitive modulations, which also highlight minute differences, infuse this cinematographic texture with its own musicality. It is integrated almost ontologically into each film like an underlying undulation where cinematic time recalls a cyclical order and ritual. This reflective dimension sheds light on his vision of art as related to the most everyday human activities, profane and sacred alike. And art is one of these activities. The cinema acts as a thread that is varyingly stretched between the levels of reality that his ample camera movements reveal in their elongation, tensions and ruptures.

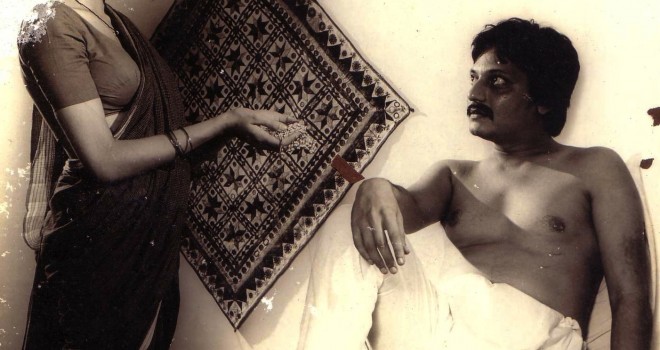

These aspects are particularly visible in Kasba (1991) and Tarang (1984), which though they differ in style more directly espouse a social, historical and political dimension. They both function on a register of fictional and melodramatic intent – and epic even in the second film. As in Maya Darpan, the rural like the industrial world seems paralysed not only due to the inertia produced by structural resistances of a patriarchal, quasi-feudal society in its decadent death throes, but also symmetrically because progressive forces are unable to turn words into action, as here again power is alive and put to effect. In this context, the relations of authority and economic control of the family structure and the roles conferred on each by tradition or social status are reframed as they crack apart before our eyes. These alienating microcosms, meticulously described and observed, reveal the weight of inaction that curbs the characters’ desire to find the path of salutory emancipation, be it social, political or moral. Here again, Kumar Shahani revisits a register of popular culture, pushing melodrama into a predictable corner so as to better transcend it (in Tarang, people dance and sing) or distance it (in the Brechtian sense?), in Kasba.

This brief and all too furtive presentation will hopefully open up the astonishing density of a work whose major quality is to not consider the question of cinema’s function and possibilities as resolved. Kumar Shahani has never ceased to do and think about this, and we will have the pleasure of journeying with a filmmaker who has turned his experience into the principle of open learning.

Jérôme Baron